ACHAIKI IATRIKI | 2022; 41(3):154–158

Case Report

Anthi Chatziioannou1, Christina Liava1, Ilias Chitas1, Charalmpos Antachopoulos2, Emmanouil Sinakos1

14th Medical Department, Hippokratio Hospital, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece,

23rd Pediatric Department, Hippokratio Hospital, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece

Received: 09 Jun 2022; Accepted: 06 Sep 2022

Corresponding author: Emmanouil Sinakos, Hippokratio Hospital, 49, Konstantinoupoleos Str, Thessaloniki, Greece, 54642, Tel.: +30 6944912668, E-mail: esinakos@auth.gr

Key words: Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

Abstract

Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C) is an emerging clinical entity which was first described in the pediatric population in April 2020. MIS-C syndrome can occur in children and teens under 21 years of age and is characterized by hyperinflammatory illness and severe extrapulmonary multiorgan dysfunction, particularly cardiovascular, occurring within 2 to 6 weeks of antecedent coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) or exposure to a person with diagnosed COVID-19 in the past month. We report a case of an 18-years-old Asian male, vaccinated for SARS-CoV-2 and with a history of COVID-19 44 days ago, that was admitted to the emergency department with persistent fever, pharyngeal pain, nausea and vomiting. Clinical examination revealed skin rash all over the body, bilateral conjunctival injection, pharyngeal erythema, lip redness and swelling. Laboratory tests and imaging revealed myocarditis, elevated inflammatory markers, liver and kidney dysfunction, bilateral ground-glass opacities at lung bases, ascites and lymphadenopathy. Thorough investigation ruled out infectious causes and a diagnosis of MIS-C was made, as all six criteria were fulfilled. Intravenous immunoglobulin and methylprednisolone were administered along with aspirin. After 5 days of treatment the patient showed prompt clinical and laboratory improvement and was discharged. MIS-C is rarely seen in vaccinated children and adolescents after SARS-CoV-2 infection. It is still unknown whether the type of COVID-19 vaccine or the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 may play a role in the development of MIS-C. Physicians and not only pediatricians should be aware of this rare clinical entity, as it has also been described in adults (MIS-A).

INTRODUCTION

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) led to millions of new cases every day and up to 5 million deaths worldwide. A rare but serious complication of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection in children and adolescents was first described in April 2020, known as Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C) [1]. MIS-C is an emerging clinical entity that can occur in children and teens under 21 years of age and is characterized by hyperinflammatory illness and severe extrapulmonary multiorgan dysfunction, particularly cardiovascular, occurring within 2 to 6 weeks after SARS-CoV-2 infection [2]. MIS-C is mainly reported in unvaccinated children and adolescents. However, a recent study found a small number of vaccinated individuals aged 12-20 years diagnosed with MIS-C, most of them with laboratory evidence of past or recent SARS-CoV-2 infection [3]. We report a case of MIS-C in an 18-years-old Asian male, who was diagnosed with mild COVID-19 in August 2021 and had received one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine (Ad26.COV2. S; Janssen) in June 2021.

CASE PRESENTATION

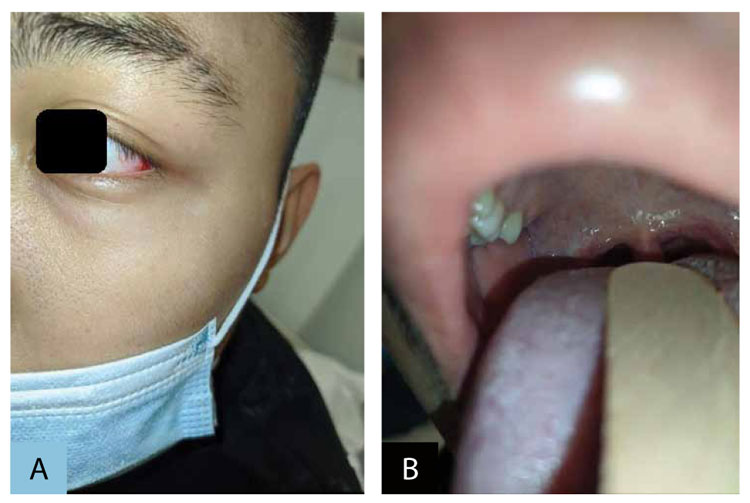

An 18-years-old Asian male was admitted to the emergency department with persistent fever (>38°C for the last 72 hours), pharyngeal pain, nausea and vomiting. Clinical examination revealed a skin rash all over the body, bilateral conjunctival injection, pharyngeal erythema, lip redness and swelling (Figure 1, Figure 2). The patient had been in his usual state of health until 3 days before admission, when fever developed, with a temperature of up to 39.6 °C, associated with the skin rash. He started azithromycin after consultation with his primary care physician. The patient had a history of SARS-CoV-2 infection first diagnosed on 23rd August 2021 (laboratory confirmed with antigen test) and received one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine (Ad.26.COV2.S; Janssen) on 30th June 2021. Furthermore, he had a medical history of asthma. He was a non-smoker and did not use alcohol. Medications included salbutamol and budesonide/formoterol for inhalation.

Figure 1. A, B: Skin rash all over the body associated with itch.

Figure 2. A: Conjunctival injection. B: Pharyngeal erythema, lip redness and swelling.

On examination, body temperature was 37.8°C, blood pressure was 99/38 mm Hg, heart rate was 98 beats per minute, respiratory rate was 35 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation was 94% while the patient was breathing ambient air. The patient had moderate shortness of breath and diffuse coarse crackles at lung bases. Laboratory test results showed elevated inflammatory markers [White Blood Cells (WBC) 11.000 K/μL, Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) 85 mm/hr, C-Reactive Protein (CRP) 307 mg/dl, ferritin 853 ng/ml and procalcitonin (PCT) 1,24 ng/ml], elevated troponin (7648,6 pg/ml), B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) 621 pg/ml, d-dimers (3869 ng/mL) and fibrinogen (571mg/dL), as well as renal and liver dysfunction. Other laboratory test results on admission are shown in Table 1.

A chest radiograph obtained in the emergency department showed bilateral multifocal patchy opacities. Antigen test for SARS-CoV-2 infection was positive. Subsequently, two nasopharyngeal swab samples for SARS-CoV-2 with a 12hour difference revealed a negative Real-Time Reverse-Transcriptase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) result. Two liters of intravenous lactated Ringer’s solution were administered, along with ceftriaxone, doxycycline, proton pump inhibitor and bemiparin 3500IU. The patient was admitted to the hospital and was examined by a cardiologist who suggested the conduction of an echocardiogram, which revealed typical findings of myocarditis with a depressed left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) around 50%. Bisoprolol was administered. Blood cultures were obtained, followed by a detailed laboratory investigation for infectious diseases (Hepatitis A virus, B virus, C virus, Human immunodeficiency virus, Varicella zoster virus, Cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, Herpex Simplex virus, Coxsackie virus, Parvo B19 virus, Toxoplasma gondi, Mycoplasma, Legionella, B hemolytic Streptococcus), which was negative.

On hospital day 3, the fever persisted. Neck stiffness and pain along with altered mental status were noted at clinical examination. Subsequently, a lumbar puncture was conducted with no evidence of infectious diseases at cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis. A Computed Tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen, chest and brain was performed after oral and intravenous contrast administration. Findings were suggestive of bilateral groud-glass opacities at lung bases, pleural and pericardial effusion, mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy, ascites, mesenteric and retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy. The patient was examined by an infectious diseases specialist who suggested the diagnosis of MIS-C, as all six criteria were fulfilled and alternative plausible diagnoses were ruled out. Intravenous immunoglobulin, methylprednisolone and oral aspirin were administered and ceftriaxone and doxycycline were stopped.

On hospital day 7, the patient showed prompt clinical and laboratory improvement (Table 1). Echocardiogram was repeated with no findings of myocarditis and an improved estimated LVEF around 55-60%. After 8 days of hospitalization the patient was discharged. Methylprednisolone was continued for 15 days along with aspirin, until the conduction of a follow-up echocardiogram to rule out coronary artery aneurysms. At 30 days follow-up he had no suggestive findings of coronary artery aneurysms and aspirin administration was stopped. His laboratory test results were normal.

DISCUSSION

MIS-C is a rare complication of SARS-CoV-2 infection among persons younger than 21 years (occurs in less than 1% of children with COVID-19 infection) [3,7]. Herein we report a case of an adolescent with MIS-C who was admitted to the hospital for the management of an acute inflammatory syndrome. The diagnostic work-up and the management of the patient is presented in detail. Study cohorts revealed a mortality rate around 2% of MIS-C patients [4,6]. A recent epidemiological study found an overall incidence of MIS-C 5.1 persons per 1,000.000 person-months. However, the overall incidence of MIS-C was higher in SARS-CoV-2 infected patients (316 persons per 1,000.000 SARS-CoV-2 infections) [7]. Among those who did have prior health conditions across studies, the most common comorbidities were being overweight (10–39%) and having a prior history of asthma (5–18%), as in our case [8]. In most study cohorts the median age of patients with MIS-C syndrome was 9 years old with a male predominance (60%) [4,5]. Subsequently, internal medicine doctors in contrast with pediatricians are not familiar with the diagnosis and the management of this rare clinical entity which tends to increase as the COVID-19 pandemic continues. We feel that our case adds to the field as it outlines the possibility of MIS-C occurrence in young adults.

According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Health Advisory, the case definition for MIS-C syndrome is an individual aged under 21 years of age presenting with fever, laboratory evidence of inflammation, clinically severe illness requiring hospitalization, multisystem (involving at least two systems) organ involvement (cardiac, renal, respiratory, hematologic, gastrointestinal, dermatologic or neurological), with no alternative plausible diagnoses and laboratory confirmed current or recent SARS-CoV-2 infection (positive RT-PCR, serology or antigen test) or exposure to a suspected or confirmed COVID-19 case within the 4 weeks prior to the onset of symptoms[1]. Our case fulfilled all these six criteria for MIS-C. Evaluation for current or previous infection with SARS-CoV-2 is necessary in order to distinguish MIS-C syndrome from biphasic COVID-19.

Except from CDC classification there are also the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Royal College of Pediatrics and Child Health (PCRCH) diagnostic criteria. According to the WHO criteria, a child up to 19 years old with persistent fever for at least 3 days, elevated inflammation markers, evidence of COVID-19, no other obvious microbial cause of inflammation and at least two of the following clinical manifestations (rash or bilateral non-purulent conjunctivitis or muco-cutaneous inflammation signs, hypotension or shock, features of myocardial dysfunction such as pericarditis, valvulitis, or coronary abnormalities, evidence of coagulopathy and acute gastrointestinal symptoms) is diagnosed with MIS-C syndrome [13]. According to the RCPCH criteria, MIS-C syndrome is diagnosed in a child presenting with persistent fever, evidence of both inflammation and single or multi-organ dysfunction with the additional occurrence of several other features [14]. Any other microbial cause, including bacterial sepsis, staphylococcal or streptococcal shock syndromes and infections associated with myocarditis must be excluded and SARS-CoV-2 PCR testing may be positive or negative.

The patient met both WHO and PCRCH diagnostic criteria. We mainly relied on the CDC criteria as more clinical and laboratory parameters are included and consequently the diagnostic accuracy is considered higher.

MIS-C has a wide spectrum of clinical signs and symptoms, though it most commonly presents with fever (97-100%). Other commonly seen signs and symptoms include abdominal pain (69%), vomiting (67%), diarrhea (54%), skin rash (55%), conjunctival injection (55%), shortness of breath (28%), mucocutaneous lesions (23%), neck pain (22%), altered mental status (11%), and, in severe cases, hypotension (52%) and cardiovascular involvement (80%). Among laboratory markers of inflammation, CRP and ferritin were frequently elevated (99% and 87%, respectively) [5,8]. MIS-C may be associated with acute kidney injury in one-in-five cases and is characterized by a self-limiting time course, as noted in our patient [11]. An epidemiological study revealed that nearly all MIS-C patients who had serologic testing for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies performed tested positive (98%), almost half had SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR positive (53%) and 67% had a positive viral antigen test [5]. Our patient had an antigen test for SARS-CoV-2 positive, but two RT-PCR negative results.

Imaging studies found that MIS-C associated with COVID-19 is characterized by cardiovascular abnormalities, although solid visceral organ, gallbladder, and bowel abnormalities as well as ascites are also seen, reflecting a multisystemic inflammatory process, as in our case [10]. While there are currently no standard clinical practice guidelines regarding treatment for MIS-C, current management and treatment plans have generally yielded favorable outcomes. Similar to standard Kawasaki Disease (KD) treatment, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) therapy was the most commonly reported treatment provided to patients (55–100%), followed by corticosteroids (10–96%), aspirin and anticoagulation therapy, as were administered in our patient. In severe cases mechanical ventilation has also been reported [5,12].

Current studies support the hypothesis that SARS-CoV-2 may act as a trigger or immunomodulatory factor in MIS-C pathogenesis, however the exact mechanism is still unknown. Eliminating the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 not only serves to prevent COVID-19 but also presents an effective strategy for MIS-C prevention [9]. A recent study found that MIS-C without evidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection is rare after COVID-19 vaccination (reporting rate lower than 1 per million vaccinated individuals aged 12–20 years) [3]. Our patient was vaccinated and after mild SARS-CoV-2 infection he was diagnosed with MIS-C. It is still unknown whether the type of COVID-19 vaccine or the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 may play a role in the development of MIS-C.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, MIS-C is a rare but serious condition which is associated with previous SARS-Cov-2 infection in most children and adolescents and rarely seen in vaccinated individuals, as in our case. Physicians and not only pediatricians should be aware of this rare clinical entity, as it has also been described in adults (MIS-A). The transmission of SARS-CoV-2, the emergence of potentially more severe and highly transmissible variants, such as the Delta variant, and the number of unvaccinated individuals is likely to have contributed to the increased incidence of MIS-C following increased SARS-CoV-2 transmission all over the world.

Conflict of interest disclosure

None to declare.

Declaration of funding sources

None to declare.

Author Contributions

Anthi Chatziioannou, Christina Liava, Chitas Ilias, Antachopoulos Charalampos and Emmanouil Sinakos conceived the research idea; Anthi Chatziioannou and Christina Liava drafted the paper; Emmanouil Sinakos also reviewed the manuscript for its intellectual content.

REFERENCES

1. Riphagen S, Gomez X, Gonzalez-Martinez C, Wilkinson N, Theocharis P. Hyperinflammatory shock in children during COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2020;395(10237):1607-8.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) associated with coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19). CDC Health Alert Network 2020.

3. Yousaf AR, Cortese MM, Taylor AW, Broder KR, Oster ME, Wong JM, et al. Reported cases of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children aged 12-20 years in the USA who received a COVID-19 vaccine, December, 2020, through August, 2021: a surveillance investigation. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2022;6(5):303-12.

4. Feldstein LR, Rose EB, Horwitz SM, Collins JP, Newhams MM, Son MBF et al. Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in U.S. Children and Adolescents. N Engl J Med 2020; 383(4):334-46.

5. Miller AD, Zambrano LD, Yousaf AR, Abrams JY, Meng L, Wu MJ, et al. Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children-United States, February 2020-July 2021. Clin Infect Dis 2022; 75(1):e1165-75.

6. Dionne A, Son MBF, Randolph AG. An Update on Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children Related to SARS-CoV-2. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2022; 41(1): e6-9.

7. Payne AB, Gilani Z, Godfred-Cato S, Belay ED, Feldstein LR, Patel MM, et al. Incidence of Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children Among US Persons Infected With SARS-CoV-2. JAMA Netw Open 2021; 4(6):e2116420.

8. Rafferty MS, Burrows H, Joseph JP, Leveille J, Nihtianova S, Amirian ES. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) and the coronavirus pandemic: Cuurent knowledge and implications for public health. J Infect Public Health 2021; (14):484-94.

9. Sacco K, Castagnoli R, Vakkilainen S, Liu C, Delmonte OM, Oguz C, et al. Immunopathological signatures in multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children and pediatric COVID-19. Nat Med 2022;28(5):1050-62.

10. Blumfield E, Levin TL, Kurian J, Lee EY, Liszewski MC. Imaging Findings in Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C) Associated With Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19). AJR Am J Roentgenol 2021; 216(2):507-17.

11. Ricci Z, Colosimo D, Cumbo S, L’ Erario M, Duchini P, Rufini P, et al. Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children and Acute Kidney Injury: Retrospective Study of Five Italian PICUs. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2022; 23(7):e361-5.

12. McArdle AJ, Chir B, Vito O, Patel H, Seaby EG, Shah P, et al. Treatment of Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children. N Engl J Med 2021; 385(1):11-22.

13. World Health Organization. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children and adolescents with COVID-19. World Health Organization Network 2020

14. Royal College of Pediatrics and Child Health. Guidance: Paediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome temporally associated with COVID-19. Royal College of Pediatrics and Child Health Network 2020