ACHAIKI IATRIKI | 2025; 44(1):21–31

Review

Ermioni Papageorgiou1, Anthi Tsogka1,2, Odysseas Kargiotis1

1Stroke Unit Metropolitan Hospital, Piraeus, Greece

2Second Department of Neurology, “Attikon” University Hospital, School of Medicine, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece

Received: 28 Mar 2024; Accepted: 03 Jul 2024

Corresponding author: Odysseas Kargiotis, Metropolitan Hospital, Eleftheriou Venizelou-1, 18547, Piraeus, Greece. Tel.: +30 2104809788, e-mail: kargiody@gmail.com

Key words: Angiitis, stroke, angiography, biopsy, central nervous system

Abstract

Primary angiitis of the Central Nervous System (PANCS) stands out as a particularly demanding neurological disorder, presenting obstacles in both the diagnostic process and the subsequent treatment strategies. Two subtypes of PACNS have been described in medical literature: small vessel disease typically diagnosed by biopsy and large/medium-vessel disease typically diagnosed through angiography. Clinical manifestations vary widely, with most laboratory and imaging tests demonstrating low specificity in the diagnostic process. In clinical practice, brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is typically abnormal and further confirmation through histopathological or angiographic assessment is required. It is essential to differentiate PACNS from many inflammatory, infectious, vascular, and malignant neurological conditions that present similar clinical manifestations in order to ensure a definite diagnosis. Treatment strategies are developed based on prolonged administration of corticosteroids combined with immunosuppressive agents. As evidence arises only from observational data, a multidisciplinary team approach in a specialized center is recommended. Multicenter prospective clinical trials are also needed to standardize the diagnostic techniques and determine the optimal therapeutic strategies.

INTRODUCTION

Primary Angiitis of the Central Nervous System (PANCS) is an uncommon neurological condition characterized by targeted inflammation of the small to medium-large vessel of the brain and/or spinal cord [1]. Although PANCS was first described by Harbitz in 1922 [2], the diagnostic process and treatment remains challenging, due to limited specificity of both its clinical manifestations and its primary diagnostic tests.

PACNS has an annual incidence of 2.4 cases per 1 million person-years with an equal sex distribution [3], while the condition affects predominantly median-aged patients, typically around 50 years of age [4]. According to Calabrese and Mallek, who first proposed diagnostic criteria in 1988, the diagnosis of PANCS is based on the presentation of a neurological or psychiatric manifestation along with characteristic angiographic or histopathological findings, while ruling out any other systemic vasculitis or other condition demonstrating similar clinical or imaging features [5]. Consequently, Birnbaum and Hellman proposed a revision of the previous diagnostic criteria in 2009, due to the necessity of distinguishing PANCS from Reversible Vasoconstriction Syndrome (RCVS) and other similar clinical conditions [6]. According to these criteria the terms “definite” and “probable” were suggested to define the strength of PANCS diagnosis. A “definite” diagnosis required histopathological evidence of vasculitis on cerebral biopsy, while “probable” diagnosis required the combination of a high-probability angiographic pattern with Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis indicating PACNS.

A probable diagnosis is considered when the following findings emerge on angiography [7]:

- Cerebral arterial areas with a pattern of smooth-wall stenosis followed by vessel dilatation

- Multiple arterial stenoses/occlusions

- Absence of proximal vessel atherosclerosis or other abnormalities

Based on the size of the affected arteries, PANCS can be categorized into two distinct types: small vessel disease (SV PANCS) and large/medium vessel disease (LV PANCS) [8]. Concordance between positive biopsy and positive angiography is observed in the minority of patients (<20%), probably reflecting the pathophysiological differences between LV-PACNS and SV-PACNS [3,9]. According to the current diagnostic criteria [6], SV-PACNS can be diagnosed only by biopsy, as Digital Subtraction Angiography (DSA) can detect abnormalities only in large and medium-sized cerebral vessels. Therefore, SV-PACNS diagnosis always meets the criteria of definite PACNS. Only LV-PACNS can correspond to probable PACNS [10,11].

In December 2023, the European Stroke Organization (ESO) published the first European guidelines on PACNS diagnosis and management, in order to establish an optimal approach in PANCS diagnosis and treatment [12]. A collaborative study group of specialists addressed 17 queries regarding SV-PANCS and LV-PANCS diagnosis and treatment. The lack of evidence-based diagnostic and treatment protocols emphasized the necessity for the development and implementation of standardized brain and vessel imaging examinations to enhance the diagnostic and therapeutic yield.

The aim of this narrative review is to outline current diagnostic and therapeutic algorithms in PACNS and to underline the importance for ongoing research on this rare neurological disease. We conclude by emphasizing the critical role of a multidisciplinary team approach in specialized centers for patients presenting with suspected PACNS [12].

DIAGNOSTICS

In medical daily practice PACNS’ diagnosis is based on a combination of clinical, laboratory and neuroimaging findings, with brain biopsy remaining the gold standard as a diagnostic tool. However, biopsy is an invasive surgical procedure and carries the risk of a non-diagnostic or false (positive or negative) results [13-15].

Clinical

PACNS presents a wide variety of clinical symptoms, many of which are non-specific. Sarti et al, conducted a review of 24 case series with a total of 585 patients and categorized the clinical features into two groups, based on their frequency: major (≥42.7%) and minor (<42.7%). Major clinical features of PACNS include new onset or altered headache, focal neurological deficits, stroke/TIA, and subacute cognitive impairment, while minor clinical features comprise seizures, altered level of consciousness, and psychiatric disturbances. To suspect PACNS, the authors suggested that one clinical and one major neuroradiological or two clinical and one minor neuroradiological feature should exist and that other differential diagnostic considerations should be excluded. Major neuroradiological findings encompassed multiple parenchymal lesions with vessel occlusion, vessel wall enhancement and parenchymal or meningeal contrast enhancement, while hemorrhagic lesions and/or a single parenchymal lesion were considered as minor features [16].

PANCS clinical manifestations are diverse, most often subacute or chronic and insidious. However, acute symptomatology may occur occasionally [17]. The occurrence of thunderclap headache, i.e., very severe, explosive, abrupt onset headache reaching its maximum intensity within < 1 minute, may also be a feature of RCVS [18]. Clinical scenarios that arouse suspicion are subacute encephalopathy of unknown etiology, meningitis after exclusion of infection and neoplasms, and multiple ischemic strokes in different vascular territories. In a retrospective analysis of 187 patients of rapidly progressive dementia, [19], PACNS comprised 5.3% of cases. Often, the most common clinical manifestations are not present in some cases [3].

Imaging

Conventional brain MRI reveals abnormal findings in nearly all patients with PACNS [20]. MRI demonstrates high sensitivity of approximately 90-100% [6,21-23]. However, findings are nonspecific and include [12]:

- Acute/subacute infarcts, either single or multiple and affecting multiple arterial territories

- Small vessel disease (SVD)

- Intracerebral Hemorrhage (ICH)

- Subarachnoid Hemorrhage (SAH)

- Tumefactive pattern (t-PACNS)

- Parenchymal contrast enhancement

- Spinal cord involvement

- Leptomeningeal enhancement

The working group of the recent ESO guidelines [12] extracted data from 18 studies conducted between 1987 and 2020 that examined patterns of parenchymal abnormalities on MRI. Parenchymal contrast enhancement was the most frequent neuroimaging pattern (20.4%), followed by multiple ischemic lesions (18.6%). An ICH/SAH pattern was reported in 13.6%. SVD pattern was probably underreported (8.8%), and a single ischemic lesion pattern was found in 6.4%. The pseudotumoral pattern was rare (4.1%), and spinal cord involvement was even rarer (0.8%). The expert consensus committee concluded that there is no specific neuroimaging pattern of parenchymal signal change that can be attributed to any PACNS subtype. Therefore, it is questionable whether the description of neuroimaging patterns is crucial for the diagnosis [12].

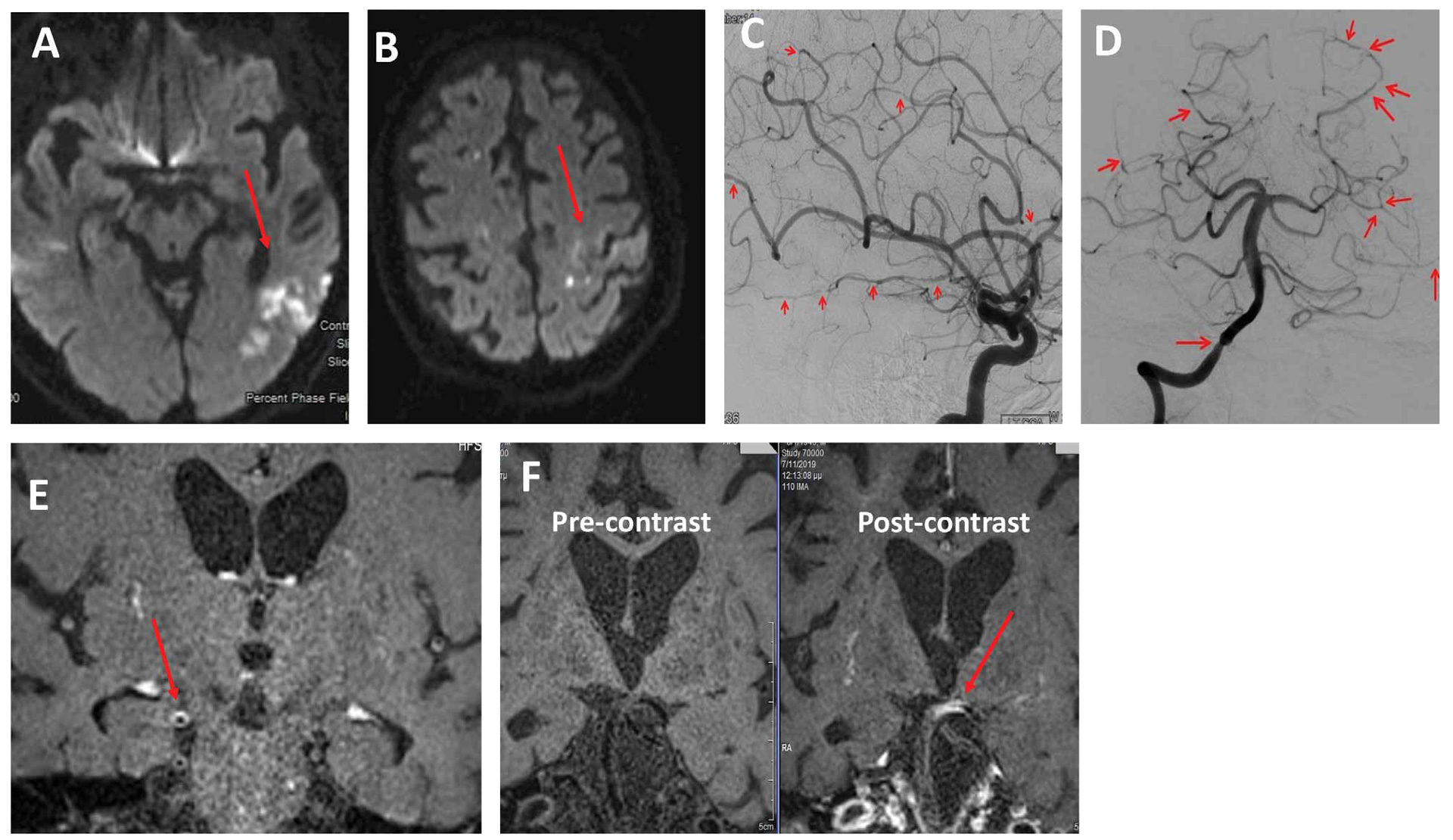

During the last years, 3D-High Resolution Vessel Wall Imaging-MRI (HRVWI-MRI) has enabled the visualization of the vessel wall in three dimensions, thus facilitating the detection of internal pathological signs within it [24,25] (Figure 1). This MRI technique has been increasingly used to differentiate PACNS from intracranial atherosclerotic disease and other inflammatory or non-vasculopathies, by demonstrating concentric vessel wall enhancement (VWE) in the stenotic arteries. Although it seems a promising technique, further validation is needed, highlighting the necessity of combining the results with other imaging modalities in order to reach a diagnosis [12].

Figure 1. A 73-year-old male was transferred to our department with an eight-day history of limb weakness and gait unsteadiness. His medical history was remarkable for colon cancer surgically treated 20 years ago, coronary heart disease and diabetes. Neurological examination revealed paraparesis and left arm ataxia. Brain MRI demonstrated multiple infarcts of different time points and in several arterial territories (acute ischemic lesions in the left temporal lobe and subacute middle/anterior watershed ischemic lesions) (Panel A). An embolic mechanism was suspected, and a transesophageal echocardiogram demonstrated a mobile atheromatous plaque in the ascending aorta. The patient received double antiplatelet therapy (aspirin and clopidogrel) and rosuvastatin. Nine days later, he developed right facial palsy, right hemiparesis, and bilateral upper limb ataxia. A new MRI scan demonstrated new acute infarcts in the right parietal lobe and the left precentral area (Panel B) as well as prominent leptomeningeal enhancement. An extensive panel of blood test examinations were within normal limits. CSF protein concentration was 170mg/dl, and the rest of the CSF analysis was normal. DSA demonstrated the involvement of multiple large and medium-sized vessels, with multiple alternating areas of vessel stenosis and dilatations (Panels C&D). 3D HRVWI-MRI showed concentric vessel wall enhancement in the multiple stenotic arteries, namely the middle cerebral arteries and the basilar artery (Panels E&F). PACNS diagnosis was established based on the currently available diagnostic criteria and the patient was treated with 1g intravenous methylprednisolone for five days followed by oral prednizolone 100mg/day and monthly intravenous CYC pulse doses. However, his situation continued to deteriorate, so rituximab infusion as a rescue therapy was introduced, but unfortunately without significant response to treatment. This is a case of highly active and aggressive PACNS with minimal response to first- and second-line treatment regimens.

Non-invasive vascular imaging techniques, i.e., Cerebral Computed Tomographic Angiography (CTA) and Magnetic Resonance Angiography (MRA), have been increasingly utilized in recent years, while the implementation of DSA has been declining [12]. It is suggested that DSA, a less invasive procedure than brain biopsy, should be considered for all patients suspected of having PACNS, when MRA or CTA fail to indicate a high probability pattern and the clinical symptoms strongly suggest the presence of PACNS. DSA represents the gold standard technique for disclosing medium-sized vessel involvement in PACNS. Regarding CTA, its multislice technique exhibits similar diagnostic yield with MRA. Nevertheless, comparative analyses between the two imaging techniques are lacking. DSA remains the gold standard in PACNS diagnosis involving large and medium sized vessels, with a sensitivity reaching 70%, but a poor specificity as low as 30% [21,26]. The main limitations of DSA are its relatively low specificity and its limited sensitivity for SV-PACNS.

Biopsy

According to Birnbaum’s criteria, SV-PACNS diagnosis requires a positive biopsy, whereas histopathological confirmation is needed in order to conclude to a “definite” PANCS diagnosis [12]. Biopsy exhibits sensitivity between 53-74%, and specificity between 90-100%, particularly when areas of imaging abnormalities are examined [1,27]. Although a negative biopsy cannot entirely rule out the diagnosis, it may be helpful to exclude PANCS mimics, especially infections and malignancies [17,28]. However, it should be noted that the histological features may resemble that of secondary vasculitis or of other immune-mediated inflammatory diseases [29]. The diagnosis is established through the identification of transmural lymphocytic infiltration and vascular wall destruction [30]. The literature describes the presence of three histopathological types: granulomatous (58%-27% of these cases associated with β-A4 amyloid deposition), lymphocytic (28%) and necrotizing (14%) [28].

Brain biopsy is an even less commonly used method to diagnose PACNS in clinical practice. This is due to the requirement for a surgical procedure and the fact that angiographic patterns are often highly indicative of PACNS [12]. Controversy exists about the utility of biopsy due to a high rate of false negative results, the risk of complications associated with an invasive diagnostic method, and the lack of standardized protocols. However, if all other diagnostic imaging methods do not yield a definitive diagnosis, a stereotactic brain biopsy should not be delayed in PACNS suspected cases. Samples from the meninges, superficial cortex, and lesion sites should be preferred to increase the diagnostic yield. Targeting acute gadolinium-enhancing MRI lesions may further improve the diagnostic process. If the affected lesion is not accessible for surgery, it is recommended to perform a biopsy from the non-dominant right frontal lobe [29].

The ESO guidelines highlight the requirement of CNS biopsy when SV-PANCS is speculated. Before proceeding to biopsy, DSA should be undertaken to demonstrate possible medium sized vessel involvement. SV-PACNS is associated with more gadolinium-enhancing lesions and fewer acute cerebral infarctions on MRI, compared to LV-PACNS. For patients exhibiting vascular abnormalities on DSA, CTA or MRA, a specialized medical team should be recruited in order to design a personalized management, including the assessment of the necessity for a brain biopsy. 12].

Laboratory tests and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis

As with clinical manifestations, there is no single laboratory test available to diagnose PACNS [22]. Therefore, the laboratory investigation involves a comprehensive screening of serological and immunological parameters, along with CSF analysis to rule out other potential diagnoses, such as infections, rheumatological diseases, and malignant disorders [1,17,21,32].

Lumbar puncture should be performed in all patients, as CSF is found abnormal in 80-90% of biopsy-proven PACNS [33]. Typically, CSF reveals mild lymphocytic pleocytosis (defined as >5 cells/ml) and/or elevated protein levels (defined as protein >45 mg/dl). Occasionally, oligoclonal bands or immunoglobulin IgG synthesis can be detected [21,34-35]. To exclude malignant vasculitis, CSF cytology and flow cytometry should be performed. If the number of cells exceeds 200/ml, an infection might be present and further analysis is required.

After analyzing data from 17 case-series and cross-sectional studies involving 763 patients, the ESO working group determined the sensitivity (77.7%), specificity (68.3%), positive predictive value (PPV: 86.6%), negative predictive value (NPV: 53.6%), and diagnostic accuracy (75.1%) of abnormal CSF analysis in PACNS patients. The working group determined that in addition to cell count and protein concentration measurement, oligoclonal bands detection and cytological analysis should be conducted. Results within the normal range should not solely exclude PACNS [12].

Differential diagnosis

An important non-inflammatory differential diagnosis to PACNS is RCVS. Formerly called benign angiopathy of the CNS [36], it occurs more frequently in young women, often presenting with sudden onset of focal neurologic deficit or thunderclap headache and is associated with a normal CSF analysis. Risk factors related to RCVS are exposure to vasoactive drugs and blood products, migraine and other headache disorders, eclampsia, pregnancy and early puerperium [37,38]. Diagnostic criteria include multifocal segmental cerebral artery vasoconstriction confirmed by angiography that must be reversed within three months, exclusion of aneurysmal SAH, a normal CSF, and severe acute headaches (“thunderclap headaches”) [37-39]. Signs of focal neurological CNS disturbances, or seizures may occur, too. RCVS may be regarded as an underdiagnosed condition, and its differential diagnosis from PACNS is extremely important since corticosteroids worsen its outcome [37]. Angiogram shows multifocal cerebral artery vasoconstriction [40]. Black blood MRI usually demonstrates a short stenosis without wall thickening or enhancement, whereas in PACNS, long concentric arterial wall thickening with gadolinium enhancement is a characteristic finding [41]. On December 2023, the REversible cerebral Vasoconstriction syndrome intERnational CollaborativE (REVERCE) project was announced in European Stroke Journal, a prospective international observational study across multiple hospitals in four European and Asian countries, aiming to enhance the identification of the disease and to better understand its epidemiological and clinical characteristics [42].

Premature intracranial atherosclerosis’ prevalence increases with age and is more likely associated with vascular risk factors (i.e. diabetes, hypertension). Unlike in PACNS, CSF analysis is typically normal, the infarcts are usually restricted to a single vascular territory and 3D-HRVWI-MRI demonstrates eccentric enhancement of atherosclerotic plaques, whereas brain CT/CTA exhibits calcified proximal cerebral arteries with irregular focal stenosis [1]. Other non-inflammatory vasculopathies as fibromuscular dysplasia and moyamoya disease are easily distinguished from PACNS based on their characteristic angiographic image and their effect on extracranial and proximal intracranial cerebral arteries [1,17,21]. Intravascular lymphomatosis (IVL) is a rare and aggressive form of extranodal non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma that mainly affects elderly patients. It typically targets the brain, skin, and lungs, where malignant cells selectively invade the lumina of vessels. IVL is associated with high mortality, due to its challenging diagnostic process and its aggressiveness. Early diagnostic indicators include MRI ischemic lesions primarily located in subcortical regions, as well as elevated levels of serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), interleukins, microglobulin, and CSF protein. Apart from direct tissue examination, the diagnosis may be confirmed by CSF polymerase chain reaction analysis. [43,44]. Cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL) is a genetic disorder that presents with a variety of clinical manifestations including migraine, multiple strokes, psychiatric symptoms, seizures, motor, and cognitive deficits. Family history of stroke and dementia along with characteristic MRI features of bilateral external capsule and temporal pole hyperintensities usually raise suspicion of the diagnosis, which is further confirmed by genetic testing (NOTCH3 gene mutation) [45]. Characteristic MRI lesion topography and fundoscopic examination can contribute to the differential diagnosis of PACNS from demyelinating disorders, Susac syndrome and genetic disorders such as Hereditary Endotheliopathy with Retinopathy, Nephropathy and Stroke [21].

Importantly, infectious arteritis should be excluded, as most infectious diseases respond to antibiotic treatment. Varicella zoster virus (VZV) vasculopathy usually affects both large and small sized vessels [46]. However, in 37% of cases, VZV vasculitis affects only small-sized vessels, thus eliminating DSA’s diagnostic efficacy. It’s worth noting that a zoster rash does not always precede the clinical manifestations. Brain MRI usually demonstrates multiple cerebral infarcts at the grey-white matter junction. Confirmation of the diagnosis requires the detection of viral DNA or anti-VZV antibodies in the CSF, with the former being a more sensitive biomarker [47] (Figure 2).

Figure 2. A 76-year-old patient was admitted at our department with a two-day history of diplopia and gait disturbance. Twenty days before admission he had been treated with empiric antibiotic therapy for an upper tract respiratory infection with concurrent headache and dizziness. His medical history was otherwise unremarkable. The neurologic assessment revealed mild confusion and deterioration in time, horizontal diplopia, right central type facial nerve paresis, right sided hemiparesis, and a sensory level at C7-C8. Brain MRI disclosed an acute infarct in the left middle cerebral artery territory (Panel A). In addition, a spinal cord MRI, with contrast injection, showed two enhancing intramedullary lesions in the cervical and thoracic spinal cord levels (Panel B&C). CSF disclosed 150cells/mm and elevated protein levels (126mg/dl), therefore an empiric antibiotic therapy with ceftriaxone, acyclovir and vancomycin for meningoencephalitis was initiated. A repeat brain MRI scan two days later demonstrated multiple foci of parenchymal enhancement in the pons and the left cerebellar hemisphere (Panels D&E), as well as diffuse leptomeningeal enhancement. High dose intravenous corticosteroid treatment was also introduced. CSF flow cytometry demonstrated multiple lymphoid cells suggesting possible lymphoproliferative disease. DSA revealed no abnormal findings, excluding large and medium vessel vasculitis. Finally, anti VZV IgG antibodies at high titers were detected in the CSF, whereas CSF PCR failed to demonstrate the presence of viral DNA. The diagnosis of VZV vasculopathy and myelopathy in an immunocompetent patient without rash was made and the patient was discharged ten days later with mild neurological deficits. One year later he remains stable, without any significant disability.

Finally, PACNS should be distinguished from CNS secondary vasculitis related to rheumatological diseases. The latter typically present with systemic signs and symptoms affecting multiple organs (lungs, renal system, etc.) and are associated with elevated ESR and serum CRP, as well as specific autoantibodies that should be screened for (antinuclear, antineutrophil cytoplasmic, anti-MPO, anti-PR3) [1]. The data regarding the differential diagnosis are presented in Table 1.

Treatment

Two primary therapeutic categories exist for PANCS: induction and maintenance therapies [20]. Induction therapy aims to achieve disease remission, usually using a combination of corticosteroids and an immunosuppressive agent. The maintenance phase aims to eliminate relapses and usually requires the addition of an immunosuppressive treatment along with corticosteroids in a tapering regimen [12]. Unfortunately, treatment is not based on randomized clinical trials [23] and is primarily derived from retrospective studies, with significant variations in the therapeutic strategies [8,12,48-50]. The clinical advantage of combining immunosuppressants and steroids still remains unclear. Given the potential severity as well as the relapsing course of PACNS, the ESO working group suggested adding an immunosuppressant to corticosteroid therapy to minimize the side effects from long-term corticosteroid administration. Developing a treatment protocol that is customized to the patient’s specific clinical profile and medical history is crucial for achieving optimal results. Corticosteroid monotherapy might be considered in milder disease phenotypes [12]. The optimal administration route for corticosteroids is still questionable, but some experts suggest that it depends on the disease’s initial severity [3,20,51]. Selecting the most suitable immunosuppressive agent is also a matter of debate. While cyclophosphamide (CYC) has been administered extensively, mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), studied in the Mayo Clinic series, was correlated with a better response to treatment, higher number of patients in remission off treatment, and lower disability scores [49]. Therefore, the ESO working group suggested initiation of treatment with either CYC or MMF in conjunction with corticosteroids. The decision between CYC and MMF should be personalized according to the patient’s requirements [12]. CYC is preferably administered through intravenous monthly pulses over a period of up to 1 year [50,51]. The ESO working group also encouraged the use of aspirin in patients with large/medium vessel involvement, as it was found to be positively associated with long-term remission in three retrospective studies [8,34,49].

The need for long-term use of immunosuppression is also controversial. In a Mayo clinic cohort, maintenance therapy did not appear to have any effect on long-term remission rates, however the risk of selection bias in these non-randomized studies is probably high [12,49]. In a French cohort, duration of corticosteroid treatment of approximately two years combined with prolonged immunosuppressive maintenance therapy were associated with prolonged remission and better functional status [50]. In this cohort, immunosuppression was added to corticosteroids about four months after their initiation and was continued for a mean duration of 2 years. The currently available data strongly supports the use of azathioprine as one of the favorable treatment options. Concerning patients with progressive disease who had previously received CYC or with a contraindication to CYC, rituximab proved to be highly effective [52,53]. It has been used both as induction as well as maintenance therapy [48-49,52,54-55] and demonstrated its efficacy in non-responders to azathioprine, MMF and methotrexate [49,55]. The latter is generally less preferable since it does not cross the blood-brain barrier effectively [56]. Importantly, if a patient relapses despite optimal treatment with corticosteroids and CYC, reconsidering the PACNS diagnosis is recommended [57].

Tumor necrosis factor-alpha blockers (Infliximab, Etanercept) have been also used in some patients with relapsing and/or refractory disease, but the evidence is extremely limited and only derived from isolated case reports [58-59].

Finally, the ESO working group suggested considering intravenous thrombolysis (IVT) in patients presenting with symptoms of acute ischemic stroke, according to ESO/ESMINT guidelines [12,60]. Endovascular thrombectomy (EVT) seems also a reasonable option in these patients when admitted within the eligible time window, since large vessel occlusion related stroke is typically associated with significant morbidity and mortality [12,61,62].

Prognosis

PACNS is an inflammatory vascular disease causing potentially significant morbidity and mortality [52]. Relapses may affect the 30-50% of patients, with high risk of residual disability [3,63-64]. In the Mayo clinic cohort, high disability scores and death were more frequently observed in patients with Aβ-related angiitis, cerebral infarction on initial MRI and angiographically proven large vessel involvement. In addition, advanced age and cognitive impairment at the time of the initial diagnosis were also negative prognostic factors [49]. According to Salvarani et al, PACNS represents a diverse group of diseases, each with unique clinical characteristics, outcomes, and treatment responses, depending mostly on the size of the affected vessels. Notably, LV-PACNS patients typically suffer from severe neurologic deficits, infarctions on MRI at diagnosis and have increased mortality rates, whereas SV-PACNS patients have overall better functional outcomes with lower mortality rates but have higher recurrence rates [3]. Furthermore, the granulomatous and necrotizing histological patterns are associated with more aggressive disease phenotypes [65,66]. On the other hand, the lymphocytic histological pattern has better prognosis. However, the quality of evidence is low, therefore the ESO working group suggested that histological patterns should not guide treatment decisions [12].

Amyloid-β-related cerebral angiitis (ABRA) is a PACNS subtype that primarily affects older patients [67,68]. Histopathological examination reveals granulomatous vasculitis related to β amyloid infiltrated arterial vessels walls. It is typically associated with a high frequency of cognitive dysfunction and can manifest with seizures. CSF demonstrates high protein levels and brain MRI scan may reveal contrast-enhancing leptomeningeal lesions. However, this subtype is characterized by a good prognosis if treatment with corticosteroids and CYC is initiated without delay. Cerebral angiography is often negative in these patients, and biopsy is needed to establish the diagnosis [69]. ABRA is a pathological subtype of sporadic cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA), a common degenerative small vessel disease of the brain, characterized by the cerebrovascular deposition of β-amyloid, affecting mainly the cortical and leptomeningeal vessels [70,71].

In a single-center retrospective observational study assessing relapses, remission, and long-term outcome, male sex was the only significant predictor of relapse. Favorable outcome was evident in 80% of patients after two years of immunotherapy. The study underlined the need for further PACNS subtype stratification to evaluate predictors of response [48].

However, there are some limitations in the currently available literature data concerning the disease prognosis, since a definition of favorable outcome is lacking, and since most studies have included patients with non-biopsy proven vasculitis. Mortality rate may exceed 15% within the first three years after the diagnosis, and consequently, timely treatment is crucial [57].

To monitor response to treatment and disease activity, serial brain and angiographic imaging is required and according to the disease evolution [72]. Color duplex sonography is a bedside tool that might be useful to monitor patients with cerebral artery stenosis [73,74].

CONCLUSION

PACNS is a rare inflammatory disease affecting the central nervous system, characterized by a relapsing or progressive clinical course, and associated with significant morbidity and mortality. The diagnosis is challenging since various other diseases may present with similar clinical presentations and neuroimaging findings. Although biopsy is the gold standard diagnostic method, it may be negative in patients with isolated LV-PACNS, where the diagnosis is based on angiographic modalities, mainly DSA. Due to the lack of randomized control trials, there is no conclusive data and recommendations on the diagnostic process and the therapeutic strategies. However, precise diagnosis is vital due to the need of identifying the patients requiring prolonged and aggressive treatment. A specialized medical team with expertise in PANCS should ideally orchestrate this process. Prospectively designed controlled international studies and trials are needed to promote diagnostic accuracy and ensure the development of standardized treatment protocols.

Conflict of interest disclosure: None to declare.

Declaration of funding sources: None to declare.

Author contributions: OK takes full responsibility for the data, the analyses and interpretation, and the conduct of the research. OK has full access to all the data. All authors have contributed to the manuscript and agree with its content.

REFERENCES

- Beuker C, Schmidt A, Strunk D, Sporns PB, Wiendl H, Meuth SG, et al. Primary angiitis of the central nervous system: diagnosis and treatment. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2018;11:1756286418785071.

- Harbitz, F. Unknown forms of arteritis with special reference to their relation to syphilitic arteritis and periarteritis nodosa. Am J Med. 1992; 163: 250–72.

- Salvarani C, Brown RD Jr, Christianson T, Miller DV, Giannini C, Huston J 3rd, et al. An update of the Mayo Clinic cohort of patients with adult primary central nervous system vasculitis: description of 163 patients. Medicine. 2015;94(21):e738.

- Ferro JM. Vasculitis of the central nervous system. J Neurol. 1998;245(12):766-76.

- Calabrese LH, Mallek JA. Primary angiitis of the central nervous system. Report of 8 new cases, review of the literature, and proposal for diagnostic criteria. Medicine (Baltimore). 1988;67(1):20-39.

- Birnbaum J, Hellmann DB. Primary angiitis of the central nervous system. Arch Neurol. 2009;66(6):704-9.

- Duna GF, Calabrese LH. Limitations of invasive modalities in the diagnosis of primary angiitis of the central nervous system. J Rheumatol. 1995;22(4):662-7.

- de Boysson H, Boulouis G, Aouba A, Bienvenu B, Guillevin L, Zuber M, et al. Adult primary angiitis of the central nervous system: isolated small-vessel vasculitis represents distinct disease pattern. Rheumatology 2017;56(3):439-44.

- McVerry F, McCluskey G, McCarron P, Muir KW, McCarron MO. Diagnostic test results in primary CNS vasculitis: A systematic review of published cases. Neurol Clin Pract. 2017;7(3):256-65.

- Nonaka H, Akima M, Hatori T, Nagayama T, Zhang Z, Ihara F. Microvasculature of the human cerebral white matter: arteries of the deep white matter. Neuropathology. 2003;23(2):111-8.

- Zedde M, Napoli M, Moratti C, Pezzella FR, Seiffge DJ, Tsivgoulis G, et al The Hemorrhagic Side of Primary Angiitis of the Central Nervous System (PACNS). Biomedicines. 2024;12(2):459.

- Pascarella R, Antonenko K, Boulouis G, De Boysson H, Giannini C, Heldner MR, Kargiotis O, et al European Stroke Organisation (ESO) guidelines on Primary Angiitis of the Central Nervous System (PACNS). Eur Stroke J. 2023;8(4):842-79.

- Miller DV, Salvarani C, Hunder GG, Brown RD, Parisi JE, Christianson TJ,. Biopsy findings in primary angiitis of the central nervous system. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33(1):35-43.

- Torres J, Loomis C, Cucchiara B, Smith M, Messé S. Diagnostic Yield and Safety of Brain Biopsy for Suspected Primary Central Nervous System Angiitis. Stroke. 2016;47(8):2127-9.

- Stoecklein VM, Kellert L, Patzig M, Küpper C, Giese A, Ruf V. Extended stereotactic brain biopsy in suspected primary central nervous system angiitis: good diagnostic accuracy and high safety. J Neurol. 2021;268(1):367-76.

- Sarti C, Picchioni A, Telese R, Pasi M, Failli Y, Pracucci G et al. «When should primary angiitis of the central nervous system (PACNS) be suspected?»: literature review and proposal of a preliminary screening algorithm. Neurol Sci. 2020;41(11):3135-48.

- Hajj-Ali RA, Calabrese LH. Primary angiitis of the central nervous system. Autoimmun Rev. 2012;12(4):463-6

- Day JW, Raskin NH. Thunderclap headache: symptom of unruptured cerebral aneurysm. Lancet. 1986;2(8518):1247-8.

- Anuja P, Venugopalan V, Darakhshan N, Awadh P, Wilson V, Manoj G et al. Rapidly progressive dementia: An eight-year (2008-2016) retrospective study. PLoS One. 2018;13(1):e0189832.

- Beuker C, Strunk D, Rawal R, Schmidt-Pogoda A, Werring N, Milles L, et al. Primary Angiitis of the CNS: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2021; 8(6):e1093.

- Hajj-Ali RA, Singhal AB, Benseler S, Molloy E, Calabrese LH. Primary angiitis of the CNS. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10(6):561-72

- Néel A, Pagnoux C. Primary angiitis of the central nervous system. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2009;27(1 Suppl 52):S95-107.

- Rice CM, Scolding NJ. The diagnosis of primary central nervous system vasculitis. Pract Neurol. 2020;20(2):109-14.

- Edjlali M, Qiao Y, Boulouis G, Menjot N, Saba L, Wasserman BA, et al. Vessel wall MR imaging for the detection of intracranial inflammatory vasculopathies. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2020;10(4):1108-19.

- Ferlini L, Ligot N, Rana A, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of vessel wall MRI sequences to diagnose central nervous system angiitis Front Stroke. 2022; 1:973517

- Rodriguez-Pla A, Monach PA. Primary angiitis of the central nervous system in adults and children. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2015;41(1):47-62

- Hajj-Ali RA, Calabrese LH. Diagnosis and classification of central nervous system vasculitis. J Autoimmun. 2014;48-49:149-52.

- Borcheni M, Abdelazeem B, Malik B, Gurugubelli S, Kunadi A. Primary Central Nervous System Vasculitis as an Unusual Cause of Intracerebral Hemorrhage: A Case Report. Cureus. 2021;13(3):e13847

- Junek M, Perera KS, Kiczek M, Hajj-Ali RA. Current and future advances in practice: a practical approach to the diagnosis and management of primary central nervous system vasculitis. Rheumatol Adv Pract. 2023;7(3):rkad080.

- Giannini C, Salvarani C, Hunder G, Brown RD. Primary central nervous system vasculitis: pathology and mechanisms. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123(6):759-72.

- Schmidley JW. 10 questions on central nervous system vasculitis. Neurologist. 2008;14(2):138-9.

- Deb-Chatterji M, Schuster S, Haeussler V, Gerloff C, Thomalla G, Magnus T. Primary Angiitis of the Central Nervous System: New Potential Imaging Techniques and Biomarkers in Blood and Cerebrospinal Fluid. Front Neurol. 2019;10:568.

- Salvarani C, Brown RD Jr, Calamia KT, Christianson TJ, Weigand SD, Miller DV, et al. Primary central nervous system vasculitis: analysis of 101 patients. Ann Neurol. 2007;62(5):442-51.

- Kraemer M, Berlit P. Primary central nervous system vasculitis: clinical experiences with 21 new European cases. Rheumatol Int. 2011;31(4):463-72.

- John S, Hajj-Ali RA. CNS vasculitis. Semin Neurol. 2014;34(4):405-12.

- Calabrese LH, Gragg LA, Furlan AJ. Benign angiopathy: a distinct subset of angiographically defined primary angiitis of the central nervous system. J Rheumatol. 1993;20(12):2046-50.

- Singhal AB, Hajj-Ali RA, Topcuoglu MA, Fok J, Bena J, Yang D, et al. Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndromes: analysis of 139 cases. Arch Neurol. 2011;68(8):1005-12.

- Ducros A. Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11(10):906-17.

- Calabrese LH, Dodick DW, Schwedt TJ, Singhal AB. Narrative review: reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndromes. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(1):34-44.

- Singhal AB, Topcuoglu MA, Fok JW, Kursun O, Nogueira RG, Frosch MP, et al. Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndromes and primary angiitis of the central nervous system: clinical, imaging, and angiographic comparison. Ann Neurol. 2016;79(6):882-94.

- Mandell DM, Matouk CC, Farb RI, Krings T, Agid R, terBrugge K, et al. Vessel wall MRI to differentiate between reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome and central nervous system vasculitis: preliminary results. Stroke. 2012;43(3):860-2.

- Lange KS, Choi SY, Ling YH, Chen SP, Mawet J, Duflos C, et al. Reversible cerebral Vasoconstriction syndrome intERnational CollaborativE (REVERCE) network: Study protocol and rationale of a multicentre research collaboration. Eur Stroke J. 2023;8(4):1107-13.

- Sengupta S, Pedersen NP, Davis JE, Rojas R, Reddy H, Kasper E, Greenstein P, Wong ET. Illusion of stroke: intravascular lymphomatosis. Rev Neurol Dis. 2011;8(3-4):e107-13.

- Bhagat R, Shahab A, Karki Y, Budhathoki S, Sapkota M. Intravascular Lymphoma-Associated Stroke: A Systematic Review of Case Studies. Cureus. 2023;15(12):e50896.

- Yuan L, Chen X, Jankovic J, Deng H. CADASIL: A NOTCH3-associated cerebral small vessel disease. J Adv Res. 2024;66:223-35.

- Bakradze E, Kirchoff KF, Antoniello D, Springer MV, Mabie PC, Esenwa CC, et al. Varicella Zoster Virus Vasculitis and Adult Cerebrovascular Disease. Neurohospitalist. 2019; 9(4):203-8.

- Nagel MA, Cohrs RJ, Mahalingam R, Wellish MC, Forghani B, Schiller A, et al. The varicella zoster virus vasculopathies: clinical, CSF, imaging, and virologic features. Neurology. 2008;70(11):853-60.

- Schuster S, Ozga AK, Stellmann JP, Deb-Chatterji M, Häußler V, Matschke J, et al. Relapse rates and long-term outcome in primary angiitis of the central nervous system. J Neurol. 2019 Jun;266(6):1481-9.

- Salvarani C, Brown RD Jr, Christianson TJH, Huston J 3rd, Giannini C, Hunder GG. Long-term remission, relapses and maintenance therapy in adult primary central nervous system vasculitis: A single-center 35-year experience. Autoimmun Rev. 2020;19(4):102497.

- de Boysson H, Arquizan C, Touzé E, Zuber M, Boulouis G, Naggara O, et al. Treatment and Long-Term Outcomes of Primary Central Nervous System Vasculitis. Stroke. 2018;49(8):1946-52.

- Pizzanelli C, Catarsi E, Pelliccia V, Cosottini M, Pesaresi I, Puglioli M, et al. Primary angiitis of the central nervous system: report of eight cases from a single Italian center. J Neurol Sci. 2011;307(1-2):69-73.

- De Boysson H, Arquizan C, Guillevin L, Pagnoux C. Rituximab for primary angiitis of the central nervous system: report of 2 patients from the French COVAC cohort and review of the literature. J Rheumatol. 2013;40(12):2102-3.

- Salvarani C, Brown RD Jr, Huston J 3rd, Morris JM, Hunder GG. Treatment of primary CNS vasculitis with rituximab: case report. Neurology 2014;82(14):1287-8

- Marrodan M, Acosta JN, Alessandro L, Fernandez VC, Carnero Contentti E, et al. Clinical and imaging features distinguishing Susac syndrome from primary angiitis of the central nervous system. J Neurol Sci. 2018;395:29-34.

- Patel S, Ross L, Oon S, Nikpour M. Rituximab treatment in primary angiitis of the central nervous system. Intern Med J. 2018;48(6):724-7.

- Angelov L, Doolittle ND, Kraemer DF, Siegal T, Barnett GH, Peereboom DM, et al. Blood-brain barrier disruption and intra-arterial methotrexate-based therapy for newly diagnosed primary CNS lymphoma: a multi-institutional experience. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(21):3503-9.

- Pagnoux C, Hajj-Ali RA. Pharmacological approaches to CNS vasculitis: where are we at now? Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2016;9(1):109-16.

- Salvarani C, Brown RD Jr, Calamia KT, Huston J 3rd, Meschia JF, Giannini C, et al. Efficacy of tumor necrosis factor alpha blockade in primary central nervous system vasculitis resistant to immunosuppressive treatment. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(2):291-6.

- Batthish M, Banwell B, Laughlin S, Halliday W, Peschken C, Paras E, et al. Refractory primary central nervous system vasculitis of childhood: successful treatment with infliximab. J Rheumatol. 2012;39(11):2227-9.

- Berge E, Whiteley W, Audebert H, De Marchis GM, Fonseca AC, Padiglioni C, et al. European Stroke Organisation (ESO) guidelines on intravenous thrombolysis for acute ischaemic stroke. Eur Stroke J. 2021;6(1):I-LXII

- Turc G, Bhogal P, Fischer U, Khatri P, Lobotesis K, Mazighi M, et al. European Stroke Organisation (ESO)- European Society for Minimally Invasive Neurological Therapy (ESMINT) guidelines on mechanical thrombectomy in acute ischemic stroke. J Neurointerv Surg. 2019;11(6):535-8

- Turc G, Tsivgoulis G, Audebert HJ, Boogaarts H, Bhogal P, De Marchis GM, et al. European Stroke Organisation (ESO)-European Society for Minimally Invasive Neurological Therapy (ESMINT) expedited recommendation on indication for intravenous thrombolysis before mechanical thrombectomy in patients with acute ischemic stroke and anterior circulation large vessel occlusion. J Neurointerv Surg. 2022;14(3):209.

- Salvarani C, Brown RD Jr, Christianson TJ, Huston J 3rd, Giannini C, Miller DV, et al. Adult primary central nervous system vasculitis treatment and course: analysis of one hundred sixty-three patients. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(6):1637-45.

- de Boysson H, Parienti JJ, Arquizan C, Boulouis G, Gaillard N, Régent A, et al. Maintenance therapy is associated with better long-term outcomes in adult patients with primary angiitis of the central nervous system. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2017;56(10):1684-93.

- Salvarani C, Brown RD Jr, Calamia KT, Christianson TJ, Huston J 3rd, Meschia JF, et al. Rapidly progressive primary central nervous system vasculitis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2011;50(2):349-58.

- Salvarani C, Brown RD Jr, Morris JM, Huston J 3rd, Hunder GG. Catastrophic primary central nervous system vasculitis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2014;32(3 Suppl 82):S3-4.

- Salvarani C, Brown RD Jr, Calamia KT, Christianson TJ, Huston J 3rd, Meschia JF, et al. Primary central nervous system vasculitis: comparison of patients with and without cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008;47(11):1671-7.

- Melzer N, Harder A, Gross CC, Wölfer J, Stummer W, Niederstadt T, et al. CD4(+) T cells predominate in cerebrospinal fluid and leptomeningeal and parenchymal infiltrates in cerebral amyloid β-related angiitis. Arch Neurol. 2012;69(6):773-7.

- Salvarani C, Hunder GG, Morris JM, Brown RD Jr, Christianson T, Giannini C. Aβ-related angiitis: comparison with CAA without inflammation and primary CNS vasculitis. Neurology 2013;81(18):1596-603.

- Theodorou A, Tsantzali I, Kapaki E, Constantinides VC, Voumvourakis K, Tsivgoulis G, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers and apolipoprotein E genotype in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. A narrative review. Cereb Circ Cogn Behav. 2021;2:100010.

- Theodorou A, Palaiodimou L, Safouris A, Kargiotis O, Psychogios K, Kotsali-Peteinelli V, et al. Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy-Related Inflammation: A Single-Center Experience and a Literature Review. J Clin Med. 2022;11(22):6731.

- Salvarani C, Brown RD Jr, Hunder GG. Adult primary central nervous system vasculitis. Lancet. 2012;380(9843):767-77.

- Ritter MA, Dziewas R, Papke K, Lüdemann P. Follow-up examinations by transcranial Doppler ultrasound in primary angiitis of the central nervous system. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2002;14(2):139-42.

- Hou WH, Liu X, Duan YY, Wang J, Sun SG, Deng JP, et al. Evaluation of transcranial color-coded duplex sonography for cerebral artery stenosis or occlusion. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;27(5):479-84.