ACHAIKI IATRIKI | 2025; 44(Suppl 1):28–37

Historical Report

Athanasios Diamandopoulos

Hon. Professor, Medical School Athens, M.D., Ph.D., BSc, Nephrologist/Archaeologist, Louros Foundation for the History of Medicine, Athens, Greece

Received: 30 Sep 2025; Accepted: 02 Oct 2025

Corresponding author: Athanasios Diamandopoulos, 18, St. Andew str., Romanou, Patras, Greece, 26500, e-mail: 1453295@gmail.com

Keywords: Medical society of Patras, Achaiki Iatriki, history of Greek medical societies

Introduction

I presume that the reasons I was invited by the President of the IEDEP, Professor Eleni Jelastopulu, and the Editor-in Chief of Achaiki Iatriki, Professor Christos Triantos, to contribute an article on the history of the Society and its journal, on the occasion of the latter’s fiftieth anniversary, are manifold.

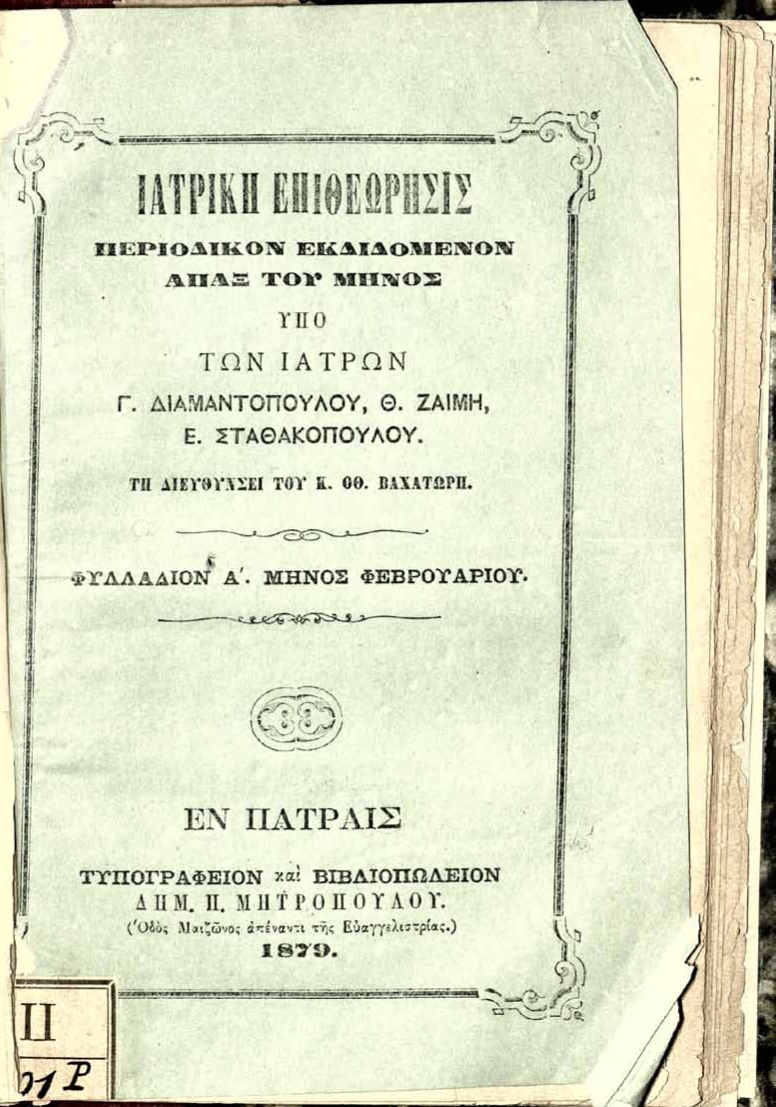

Firstly, in 1987, I had the honour of delivering the keynote address for the 75th anniversary of the Medical Society of Patras. The following year, I was similarly privileged to speak at the centenary of the first medical journal published in Patras, Iατρική Επιθεώρηση (Medical Review) (Fig. 1) The Editor-in-Chief was Othon Bachatoris, with Editorial Board members G. Diamandopoulos, Th. Zaimis, and E. Stathakopoulos. The endeavour succeeded in producing eight issues, four of which are preserved at the National Library, located in the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Centre in Athens. A similar invitation followed in 2012 for the Society’s centenary [1,2,3,4].

Figure 1. The front cover of the Iatriki Epitheorisis. Courtesy of the National Library of Greece.

These previous engagements, along with my extended tenure as President of the Society for seven years and as Editor-in Chief of Achaiki Iatriki for eighteen years, served as the catalyst for this current invitation to reflect on the Journal’s half-century of existence. I pledge to make every effort to write another such article in ten years’ time – on the occasion of the Society’s 125th anniversary and, simultaneously, my 95th birthday.

Material

The material for this article is drawn from extensive extracts of the author’s previous publications and lectures. In addition, it incorporates personal recollections from his professional experience as a physician and administrator within the National Health System (ESY), as well as from his role as a member of the IEDEP Board of Governors. Supplementary sources include entries from dictionaries and articles from newspapers relating to the medical landscape of Patras.

Inevitably, the use of such material has resulted in a personalised and self-referential account. However, this may be justified, as the present issue of Achaiki Iatriki is a commemorative one, and a focus on the activities and reflections of senior members of the Society is entirely fitting for the occasion.

Extracts from My Previous Commemorative Articles on Various Anniversaries of IEDEP and Achaiki Iatriki

a. The Journal

A special section must be devoted to the journal Achaiki Iatriki, published by the IEDEP. Almost all medical societies, both in Greece and abroad, have attempted to establish a journal. This aspiration is entirely understandable: such publications serve to inform members of the Society’s activities, encourage scholarly contributions, and provide a forum for articles of local medical interest.

However, these journals often struggle to survive and typically do so only through the self-sacrifice of their editorial directors. With the advent of digital publishing, competition has become increasingly intense, particularly for journals of general medical interest rather than specialist fields. The same challenges apply to the IEDEP’s journal, Achaiki Iatriki.

The journal was first issued in 1975 under the directorship of Alekos Maraslis. In 1978, he was succeeded by Athanasios Diamandopoulos, who served – intermittently – for approximately twenty years. Thereafter, Dr. Marianna Stamatiadou assumed the editorial role. More recently, the journal has been overseen by Nikos Kounis, under whose stewardship both its format and content have been significantly enhanced.

In place of a separate epilogue, I shall reproduce here an excerpt from the preface I wrote for the commemorative issue of Achaiki Iatriki in 1988, marking the centenary of the publication of Patras’ first medical journal, the Medical Review (Ιατρική Επιθεώρησις). In December 1878, the following declaration appeared:

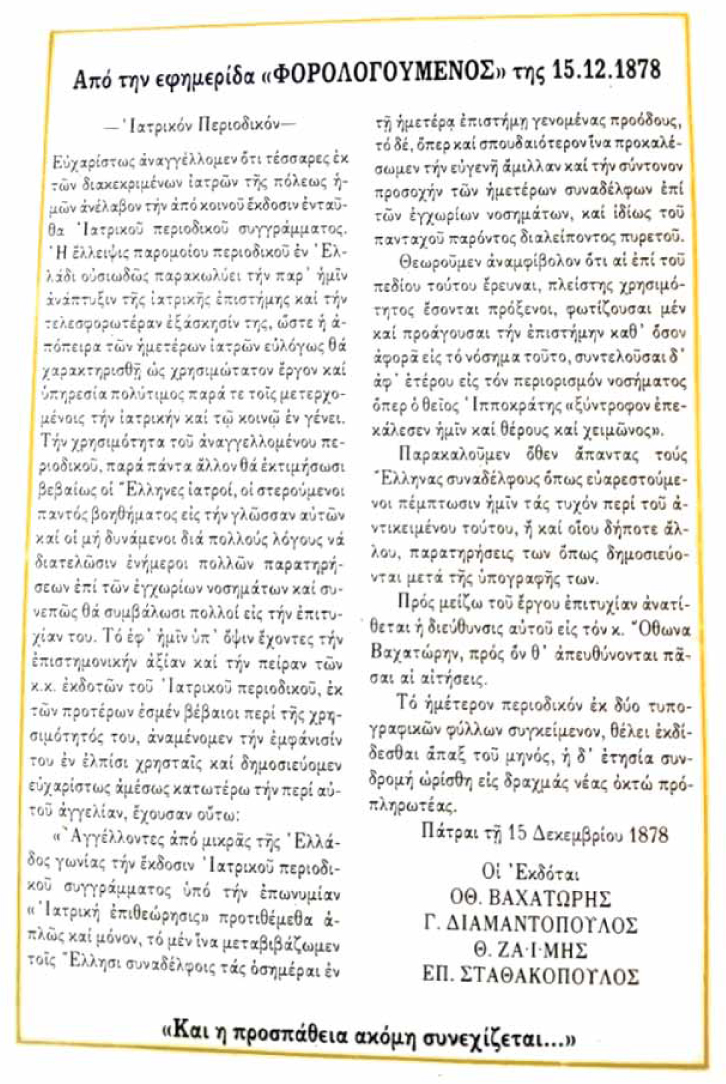

“Announcing from a small corner of Greece the publication of a medical journal under the name Medical Review, we intend simply and solely to communicate to our Greek colleagues the latest advances in our science, and, more importantly, to inspire noble competition and concerted attention towards domestic diseases, especially the omnipresent intermittent [fever]” [5] (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. The announcement about the forthcomimg publication of the 1st Medical Journal in Patras in the Phorologoumenos newspaper on the Dec 15th, 1878.

b. The Society

The period during which the Society was founded was marked by both minor local dramas and major national developments. One such personal tragedy was the suicide of the then Chairman of the Financial Committee of the Apollo Municipal Theatre – also godfather of the author’s father – which occurred in his private theatre box (according to family oral tradition). At the same time, Greece was entering a period of great national significance with the declaration of the 1st Balkan War.

The term “the Society” is used here deliberately and without further specification, as this is not the centenary of its present form, but rather the centenary of the foundation of its predecessor: the Medical Society of Patras. This was the modest sapling that, fifty-seven years later, grew into the Medical Society of Western Greece, which itself evolved, after a further twenty-five years, into the present-day Medical Society of Western Greece – Peloponnese.

Before delving further into this institutional development, it is important to explore the cultural substratum that facilitated the emergence of our local history. Cultural, historical, and indeed biological phenomena do not descend from the heavens, nor do they emerge through parthenogenesis. A common methodological error among historians is to portray their subjects as self-generated, self-sufficient, and unique, thereby distorting any proper evaluation.

On the contrary, every historical phenomenon must be contextualised in terms of both time and place. That is to say, one must examine comparable initiatives on an international scale, investigate the reasons for their emergence, and consider their failures and achievements. Only then should attention turn to other medical societies established prior to our own, both abroad and within Greece. In short: where, by whom, and how the groundwork was laid. By doing so, we shall better understand the genesis and trajectory of our own Society throughout the past century, without undue exaggeration or criticism.

The cultural movement that catalysed the widespread formation of medical societies across Europe was the Enlightenment. Centred on the dissemination of knowledge to the general public, underpinned by determinism and an aspiration to expand knowledge beyond institutionalised entities such as universities and academies, it created the ideal conditions for the establishment of scientific associations.

Among the earliest of these were the Royal Academy of Medicine in France (1730), the Medical Society of Edinburgh in Scotland, the Medical Society of London (1783), and the Royal Medical Society of London (1805). Also noteworthy are the Imperial Societies of Berlin and Vienna around 1800, and closer to our region, the Physico-Medical Society of Moscow, Russia (≤1823); the Medical Society of Bucharest (1857); the Ottoman Medical Society (1866); the Serbian Medical Society (1872); and, finally, the Medical Society of Banat, Backa, and Baranja in Vojvodina (1919).

The New World followed the example of the Old, as illustrated by the establishment of the Massachusetts Medical Society in 1781 and the New York County Medical Society in 1806. Indeed, three years prior to the founding of the IEP, the Columbia Medical Society was celebrating its 85th anniversary.

Today, medical societies in the New World have proliferated. Yet, the Old World continues to assert its cultural dominance, even abroad, as evidenced by the flourishing of medical societies based on national or ethnic origin. Below is a list of such ethnically affiliated medical societies operating solely in New York:

- American Yugoslav Medical Society

- Argentine–American Medical Society (AAMS)

- Asian–American Physician Association of Western New York

- Association of Chinese American Physicians (ACAP)

- Association of Haitian Physicians Abroad

- Association of Philippine Physicians in America

- Bangladesh Medical Association of North America

- Chinese American Medical Society

- Dominican Medical Association of New York

- Empire State Medical Association

- Hellenic Medical Society of New York (est. 1937)

- Hudson Valley Indian Physician Practitioners

- Hungarian Medical Association of America

- Iranian American Medical Association

- Janusz Korczak Medical Society

- Japanese Medical Society of America

- Korean American Medical Association of the US

- Morgagni Medical Society

- Myanmar American Medical Education Society

- National Hispanic Medical Association

- Philippine Medical Association of America

- Rajasthan Medical Alumni Association

- Romanian Medical Society of New York

- Shiraz University School of Medicine Science Alumni Association

- Society of Asian–Indian Surgeons of America

- Spanish–American Medical Society

It is worth noting that the Hellenic Medical Society of New York was established only twenty-five years after the founding of the Medical Society of Patras.

Having considered the development of medical societies abroad, often hastily and selectively, we now turn to their evolution within Greece, specifically before the establishment of the IEP. This offers a more grounded understanding of the institutional progression over time and space.

The Medical Society of Athens was founded on 13 May 1835, two years prior to the establishment of the National University. Its history has been described as synonymous with the history of modern Greek medicine. The Medical Society of Ermoupolis in Syros was founded in 1894 by the city’s residents, and its charter was ratified by Royal Decree. The Society’s stated aim was “the closest communication and cooperation of the Partners through the study and discussion of any issue concerning the interests and scientific knowledge of the sector”. The Medico-Surgical Society of Corfu was founded in 1897 by the Corfiot physicians Ilias Politis, Evgenios Pogiagos, and Petros Zotos, and continues to flourish to this day. The Medical Society of Chania arose as a product of the dynamic intellectual environment fostered by the Halepa Convention, alongside marked advancements in health care and medical science in the city. It was officially established on 28 February 1903 by local physicians.

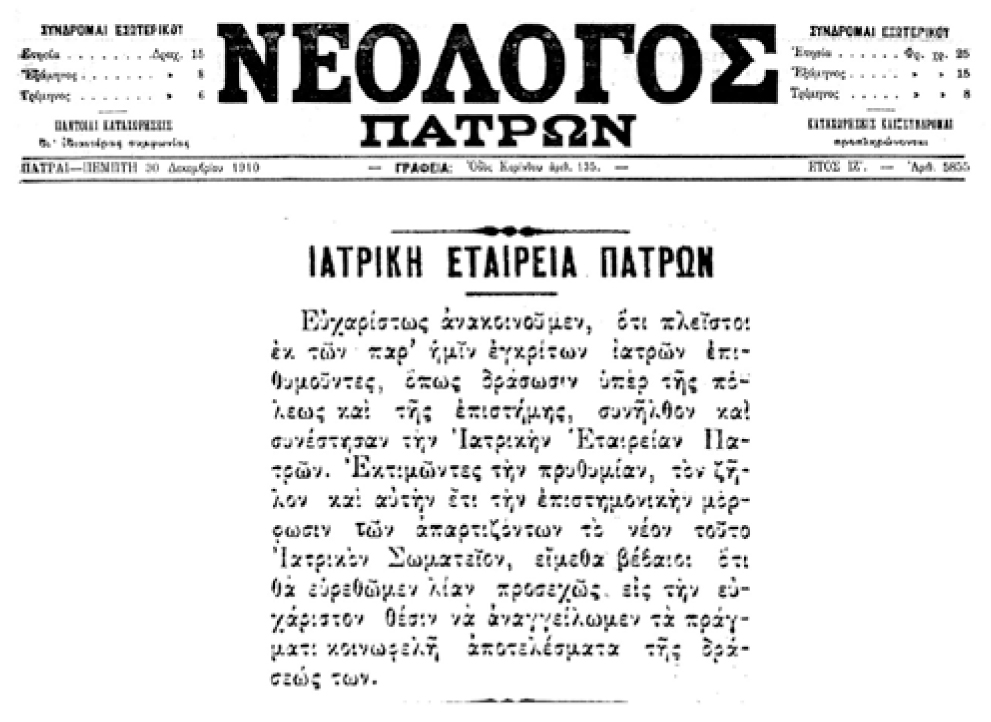

The Medical Society of Patras was founded in 1912, with a significant distinction. In the founding declaration, which was promptly published in the Neologos newspaper of Patras, it was stated: “Respected doctors of the city have resolved to establish a Medical Society of Patras in favour of the city and Science.” It was the first medical society in Greece to explicitly aim, in addition to promoting the interests of its members and of medicine more broadly, to serve the benefit of the city itself. The Society was founded at the Kanellopoulos Mansion, located at the junction of Gounari and Maizonos streets.

To conclude this section on the antecedents of the Medical Society of Western Greece and Peloponnese (IEDEP) within the landscape of Greek medical societies, it is worth correcting a persistent misconception: the IEDEP is in fact the fifth oldest such society, not the second, as mistakenly claimed on its website. Similar understandable errors occur elsewhere – for instance, the Medical Society of Chania incorrectly asserts that it was the second to be founded in the free Greek state, when it is in fact the third.

A broader observation may be made: all five of the earliest medical societies in Greece were established in port cities, marked by substantial contact with the wider world, thriving commercial activity, and a prominent bourgeois class. Notably, these were also cities without medical schools at the time. These socio-economic and geographical parameters significantly shaped the character and objectives of the Societies in question.

At that time, Patras embodied all the aforementioned characteristics, and it was therefore natural that the Society would follow the example set by its predecessors. In concluding this section, we observe that the Society has remained steadfast in its original mission, set out in 1912: to serve both the city and science. To all of us who endeavoured to contribute to its work, the experience brought particular joy and fulfilment. Yet, when those early announcements were written, the gathering storm on the horizon remained unseen. In fact, what occupied the neighbouring column of the newspaper was a report on a dance organised by the venerable Mrs. Kyriakoula Roufou-Kanakari and a circle of the Patras aristocracy, held in aid of the “Asylum for the Insane.” Among the participants was Dr. Karokis, who would take his own life a few years later in Kifissia. Also present was Dr. Ioannis Vlachos – then Mayor of Patras and cousin of Dimitris Gounaris – who, less than a decade later, would accompany his relative from imprisonment in Goudi to execution alongside the “Six”. In this way, the doctors of Patras, like most people, navigated a path between professional achievement, social prominence, and personal tragedy, contributing along the way to the advancement of medicine in Greece.

In the epilogue of my address for the Society’s 75th anniversary in 1988, I characterised the IEDE as a kind of scientific café. There, freed from formal hierarchies and careerist ambitions, members could engage in amicable or spirited discussion, always in an atmosphere of civility and ease.

Before composing the present article, I happened to come across a similar description in a historical account of British coffeehouses: “An early example of science emanating from official institutions into the public realm was the British coffeehouse. With the establishment of coffeehouses, a new public forum for political, philosophical, and scientific discourse was created. In the mid-16th century, coffeehouses cropped up around Oxford, where the academic community began to capitalise on the unregulated conversation that the coffeehouse allowed.”

In such a spirit, the members of our Society continue to gather, drawing strength from one another as they prepare to lead the Society into its second century of life [2].

The most valuable contribution of the Society, however, is that it continues to offer a forum for the friendly and informal exchange of scientific ideas – beyond institutional boundaries – among doctors from our city, from other regions of Greece, and from abroad.

Errata

The text up to this point has drawn upon excerpts from my own and others’ earlier publications, chosen for their presumed relevance to this celebratory issue. The following section seeks to correct certain inaccuracies, whether mine or others’, concerning the history of the IEDEP and its journal. In addition, I shall elaborate upon some of my earlier theses.

a. Addendum on Achaiki Iatriki

An update is warranted in relation to Achaiki Iatriki. The current Editor-in-Chief is Professor Christos Triantos, who has transformed the entire concept of the journal, and he deserves to be congratulated for this achievement. The journal is now published online and in English. While some of our more senior colleagues initially found these changes somewhat unsettling, it must be acknowledged that, overall, the innovations have been beneficial for the journal itself, and for its authors, who quite rightly hope that their publications will carry due academic weight on their curricula vitae. It is to be hoped that a mutually acceptable compromise will eventually emerge.

A further addition provides historical context regarding the financial difficulties faced by the journal when it was still issued in print. In the prologue to the first issue of 1986 [6], I, as Editor-in-Chief at the time, offered an apology for the three-year cessation of the journal’s circulation. I attributed this hiatus to the significant financial burden it imposed on the Society and announced a new collaborative agreement between the IEDE and the Medical School of Patras. Under this arrangement, the journal was to become a joint enterprise between the two institutions. The proposed Editorial Board was to comprise five members: three from the Society and two from the Medical School. The editorial team designated for the next issue was as follows: Editor-in-Chief: Athanasios Diamandopoulos, Members: Apostolos Vagenakis, Ioannis Varakis, Ioannis Karaindros, Spyros Syribeis. Although the agreement received formal approval from the Medical School’s General Assembly, it was never implemented.

One final point concerns the first medical journal published in Patras, the Medical Review. In the prologue of its inaugural issue, dated 15 December 1878, the editor of the newspaper Phorologoumenos (The Taxpayer) stated: “The usefulness of the forthcoming journal will surely be appreciated by Greek doctors, who are lacking any scientific source in their own language” [5] (Fig. 2). This comment reflects the fact that many Greek physicians at the time were not proficient in foreign languages. As a result, Greek became the language of the Medical Review, and subsequently of Achaiki Iatriki from its founding in 1975. Reflecting broader historical and linguistic shifts, the journal began to be published exclusively in English as of 2020, as previously noted.

Further Corrections and Elaboration on the Society and the Museum

i. The Founding Date of the Society

The first significant error concerns the commonly accepted founding date of the IEDEP’s predecessor, erroneously cited as 1912. This inaccuracy has led to a series of misguided anniversary celebrations. Equally incorrect was my own attempt to link the Society’s establishment with the onset of the First Balkan War. This mistake has been repeated by several authors and, regrettably, is also perpetuated on the IEDEP’s official website.

All of these accounts refer to a brief announcement published in the Neologos newspaper in 1912, yet none appear to have consulted the original source directly. The root of the confusion can likely be traced to a detailed article on the IEDE found in Alekos Maraslis’ otherwise excellent book Medicine and Doctors in Patras [7], where he specifies the date as 30 December 1912. While preparing this article, I revisited the archival issues of Neologos and discovered that the relevant announcement had, in fact, been published on 30 December 1910 (Fig. 3). It seems likely that Maraslis had noted the correct day and month but miscopied the year – a minor oversight that inadvertently “infected” the literature and institutional memory that followed.

Figure 3. The announcement about the establishment of Patras Medical Society in Neologos newspaper on Dec 10th, 1910.

The errors do not end there. Maraslis goes on, without citing sources, to suggest that the Society was established in 1912 (or possibly 1921, as hinted by a typographical slip that sets the date as 19212), yet did not become active until 1928. From that year onwards, the Society began to hold regular meetings on scientific topics, continuing until 1940, the year Greece entered the Second World War. Over this twelve-year period, thirty-six meetings took place – an average of three per year.

Another hiatus followed, which Maraslis does not date precisely. However, a careful reading between the lines suggests it lasted roughly a decade. In the elections of 1962, Georgios Bibis was elected President, followed in 1968 by Nikolaos Lagoumitzis. The latter broadened the Society’s scope, incorporating members from medical institutions in north-western Peloponnese and Aitoloakarnania. As a result, the Society was renamed IEDE (Medical Society of Western Greece).

Later, during the presidency of Andreas Mitropoulos (1998–2004), the Society expanded its geographical remit once again and adopted its current name: IEDEP (Medical Society of Western Greece and Peloponnese) [2].

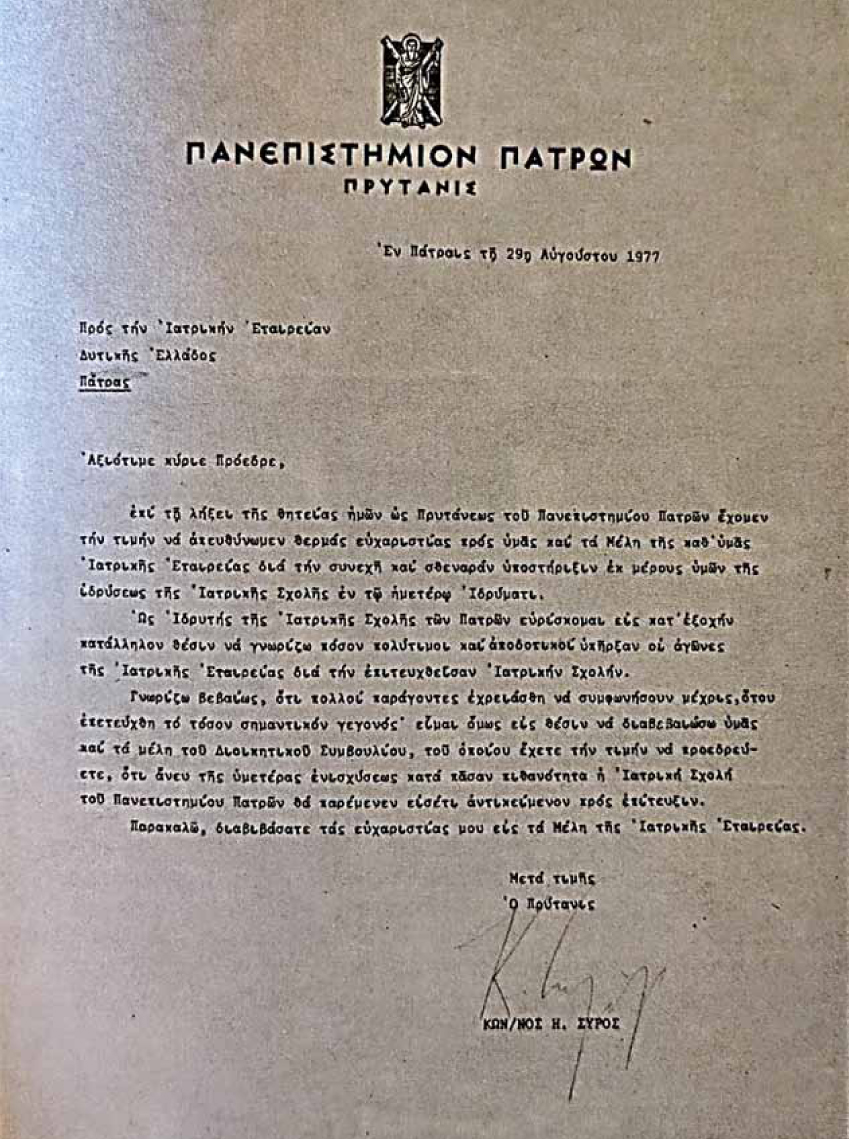

ii. The Gold Medal to the IEDE

A second claim requiring clarification concerns the purported awarding of the University of Patras’ Gold Medal to the IEDE in recognition of its strong and persistent advocacy for the University’s establishment. This statement has been repeatedly and proudly cited by IEDEP officials, myself included. However, to the best of my knowledge, no one has ever actually seen this medal. According to rumour, the late Nikos Lagoumitzis – then President of the Society – may have kept it at his residence. Yet, upon contacting his family, we were informed that they had no knowledge of its existence. The same rumour holds that the award diploma had been signed by the late Constantinos Syros, who was then Rector of the University. Maraslis, however, includes in his account a photograph of a very warm letter of thanks written by Syros and addressed to the Society, acknowledging its steadfast support for the establishment of the Medical School in 1977 – not the University as a whole (Fig. 4). It is likely that at some point, someone misinterpreted or embellished this letter, transforming it in memory into a formal award – possibly aided by the retention of the Rector’s name in association with the event. Thus, and regrettably, the so-called “Gold Medal” appears to be nothing more than an urban legend (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Thank-you letter sent to IEDE by the Rector of the University of Patras, C. Syros, in 1977, acknowledging its contribution to the establishment of the Medical School.

iii. The Birthplace of the Society

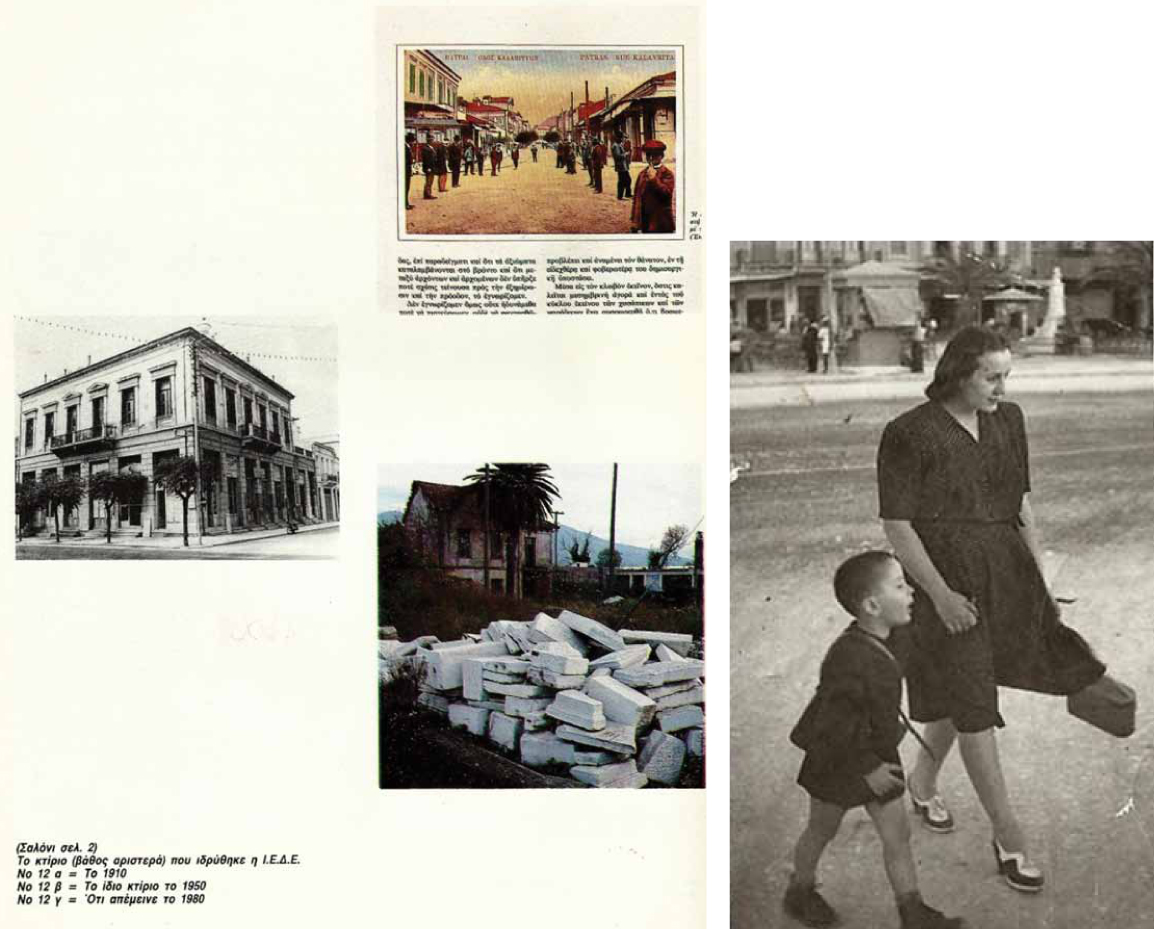

Yet another misstatement concerns the location where the founding members – described as “eminent doctors” – first convened to establish the Medical Society of Patras. The account reads: “The Society was founded at the Kanellopoulos Mansion at the junction of Gounari and Maizonos streets (Fig. 5). ”Although it has never been definitively established which member of the Kanellopoulos family the building belonged to, this article originally posited, with some justification, that the most probable candidate was the pharmacist Kanellos Anastasios Kanellopoulos: a municipal councillor, newspaper columnist, active civic participant, and relative of two Greek Prime Ministers – Dimitrios Gounaris and Panagiotis Kanellopoulos. A staunch royalist, he suffered various forms of persecution during the period of the National Schism (Dichasmos) [2, 3]. However, following further investigation, assisted by the respected journalist Tasos Stathopoulos, the actual location of the building was identified before its eventual demolition (Fig. 6). It stood in St George’s Square. Based on the historical and biographical context, the most likely venue for the Society’s founding was this building in the Upper Town, consistent with the status of pharmacist Kanellos Kanellopoulos.

Figure 5. On the left: the Kanellopoulou Mansion, where the Medical Society of Patras was founded. Upper middle: a view of Gounari Street at the time of the foundation. Lower middle: the remains of the mansion after its demolition. On the right: the author of this article, accompanied by his mother, on the way to the private nursing school later established in the mansion.

Figure 6. Patras, late 19th century. The house of Kanellos Kanellopoulos and Amalia Gounari (parents of Prime Minister Panagiotis Kanellopoulos), located in the Upper Town opposite the Ancient Odeum. Source: Pinterest, courtesy of Tasos Stathopoulos. This was most likely the house where the Patras Medical Society was founded.

iv. The X-ray Apparatus of the Old Hospital

Another misleading statement – made by myself and others – concerns the arrival of the first X-ray apparatus at the Old Hospital [8]. It has been repeatedly stated that an X-ray machine arrived at Agios Andreas Hospital in 1896 – only two years after Wilhelm Röntgen’s discovery of the eponymous radiation – thanks to a donation by the wealthy merchant Michael Kollas.

This statement is technically correct. However, the full account is rather less encouraging. Within just two years, the apparatus ceased functioning due to the lack of electricity, and its components were left prey to looters. In 1924, another affluent merchant, Nikolaos Giannopoulos, donated 300,000 drachmas, enabling the hospital to import a new radiology unit from France [9]. Unfortunately, following a series of financial scandals, the Consultant Radiologist, the late Petros Rallis, was dismissed from his post [7].

At one point, I attempted to secure this apparatus for inclusion in the future Museum of the History of Medicine. However, it was ultimately decided that the equipment should remain in situ at the hospital. Meanwhile, a similar antique device, presumably manufactured circa 1915, was generously offered to the museum by the descendants of a late radiologist. Despite my best efforts, the Board of Governors of Agios Andreas Hospital was unable to allocate the modest funds necessary for its transportation from Riga Feraiou Street to the hospital premises, so this historically valuable apparatus was lost forever for Patras.

v. The Asylum for the Lunatics

In 1916, Mayor A. Boukaouris decided to establish an Asylum for the Lunatics (Asylon ton Trellon) with the aim of providing shelter for those mentally ill individuals who were aimlessly wandering the city. To that end, a municipal building was restored and functioned as such until the Second World War [7]. Regrettably, nothing remains of the building today – not the structure itself, nor the asylum’s archives, nor any photographic documentation of the patients. I made an effort to preserve at least the marble commemorative plaque that had once stood above the entrance (Fig. 7), intending it as a testament to the existence of this early mental health institution in our city. However, I was informed by the then Head of the Department for Municipal Works that during the redevelopment of the old municipal slaughterhouses in Akti Dymeon, near which the asylum was located, the plaque had been broken and subsequently discarded. Thus, no trace of it survives.

Figure 7. The commemorative marble plaque above the entrance of the derelict “Asylum for the Lunatics.”

vi. The Abandoned Museum Project

It is now necessary to revisit a statement made in my laudatory article marking the centenary of the IEDE, in which I praised the Society’s “intense activity in securing housing for the Museum of the History of Medicine within the Old Hospital”. The campaign to establish the museum was vigorously promoted by the IEDE and, in later years, by Agios Andreas Hospital during my tenure as Vice-President of its Board of Governors. The initiative enjoyed wide-ranging support: it was endorsed by the President of the Hellenic Republic, by all local and national medical societies and colleges, by the Medical School of Patras, and unanimously by the Municipal Council of Patras during the mayoralty of Andreas Karavolas.Yet, on the very day the final agreement was to be signed, the incoming mayor, Andreas Fouras, reversed the decision. Thus, two decades of determined advocacy were nullified, and the city lost not only the opportunity to establish a medical history museum, but also the chance to expand the Apollo Theatre.

I shall refrain from commenting on the true motivations behind this abrupt reversal.

Discussion

These errors highlight the critical importance for historians of medicine – and indeed of any discipline – to consult original rather than secondary sources. Such a practice presupposes, however, that original records are preserved and valued accordingly. My own experience does not support this assumption.

During my tenure as Member of the IEDE’s Boad of Governors, my secretary, Mrs Ioanna Solomou, meticulously recorded and later transcribed all Board discussions since 1982. Over time, these records formed several volumes documenting the Society’s activities, concerns, and decisions – a valuable primary resource for future researchers. Unfortunately, in 1995, a subsequent President requested that these volumes be removed from Agios Andreas Hospital, where they were safely housed as part of a future Historical Library, and transferred to the Medical Association. A few years later, the Association’s Board deemed there was no space to retain them and discarded the entire collection.

A similar fate befell the archived volumes of Achaiki Iatriki, also in the possession of the same colleague, who eventually disposed of them as recyclable waste. Only the ten-year sets I had previously deposited with the Municipal Library have survived. Fortunately, in 1998, the junior doctors in my Clinic Grigoris Alokrios and Eleni Mitopoulou authored a paper titled Review of the History of Medical Societies and the History of the Medical Society of Western Greece, under my supervision. The study was awarded the IEDEP’s Prize in the History of Medicine and preserved several details from the now-lost minutes. The celebratory publication marking the 75th anniversary of the IEDE also serves as a useful secondary source. It is recommended that the IEDEP Board of Governors undertake to recover any remaining historical materials [2]. A similar disregard for historical preservation was evident when the Board of Governors of Agios Andreas’s Hospital sent to be pulped all the volumes of Board Minutes, spanning several decades, that I had stored in a room designated for the future Museum of the History of Medicine. This too constituted a significant loss of original documentary evidence.

The destruction was not limited to written documents. Objects of significant historical value to the study of medicine, as well as the buildings housing them, were similarly discarded or neglected. A substantial collection of medical equipment from Agios Andreas Hospital, dating from the early 20th century to the beginning of the 21st, along with numerous artefacts donated from private collections and stored in several hospital rooms, was disposed of following my retirement. The rationale cited was the now-familiar justification: “lack of space”. The same fate befell key historical assets of the old Agios Andreas Hospital, constructed in the latter half of the 19th century according to the plans of architect Theophilus Hansen. Its renowned medical library, which contained works spanning from the 18th to the 20th century, was looted by Italian occupation forces during WWII, with many volumes taken to Italy. The remaining materials were left unprotected and became vulnerable to removal or neglect by anyone within the hospital.

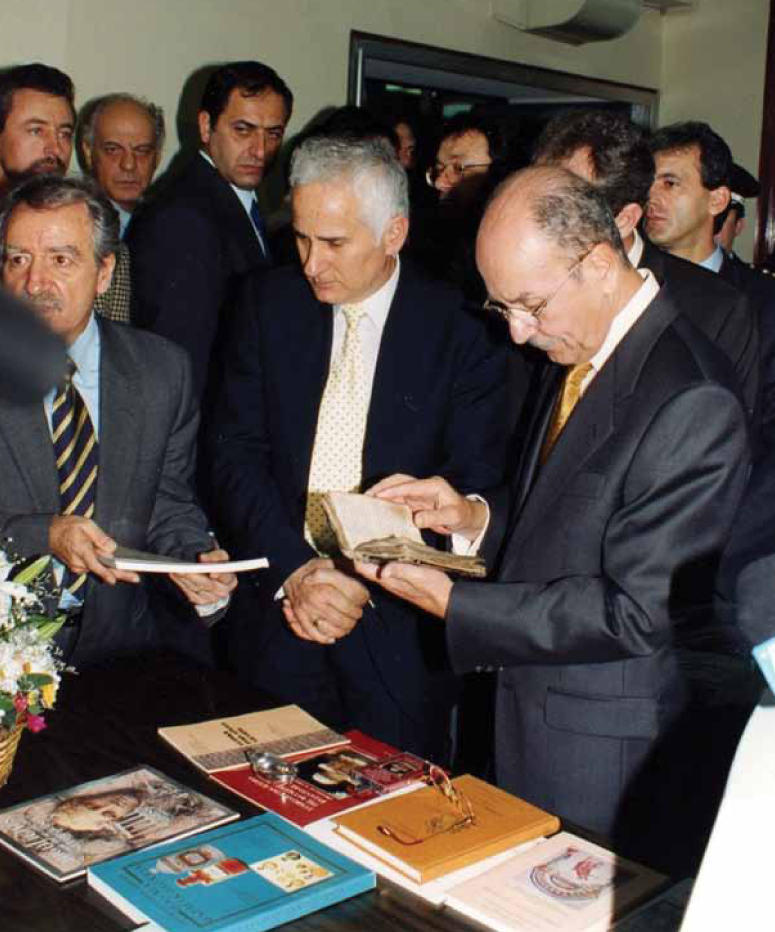

With the assistance of junior doctors in my clinic, the surviving books were eventually recovered, catalogued, assigned serial numbers, and stored in appropriate bookcases in a large room that I used as an office. The then President of the Hellenic Republic, the late Constantinos Stephanopoulos, formally inaugurated the Library of Historic Medical Books and offered it high praise (Fig. 8). However, following my departure, the bookcases were again removed – ostensibly due to “lack of space”- and the volumes dispersed to various unspecified locations. One can only hope that the marble plaque commemorating the library’s inauguration will not also be lost (Fig. 9).

Figure 8. The late Costis Stephanopoulos, President of the Hellenic Republic, at the inauguration of the Historical Books Library at St. Andrew’s Hospital.

Figure 9.

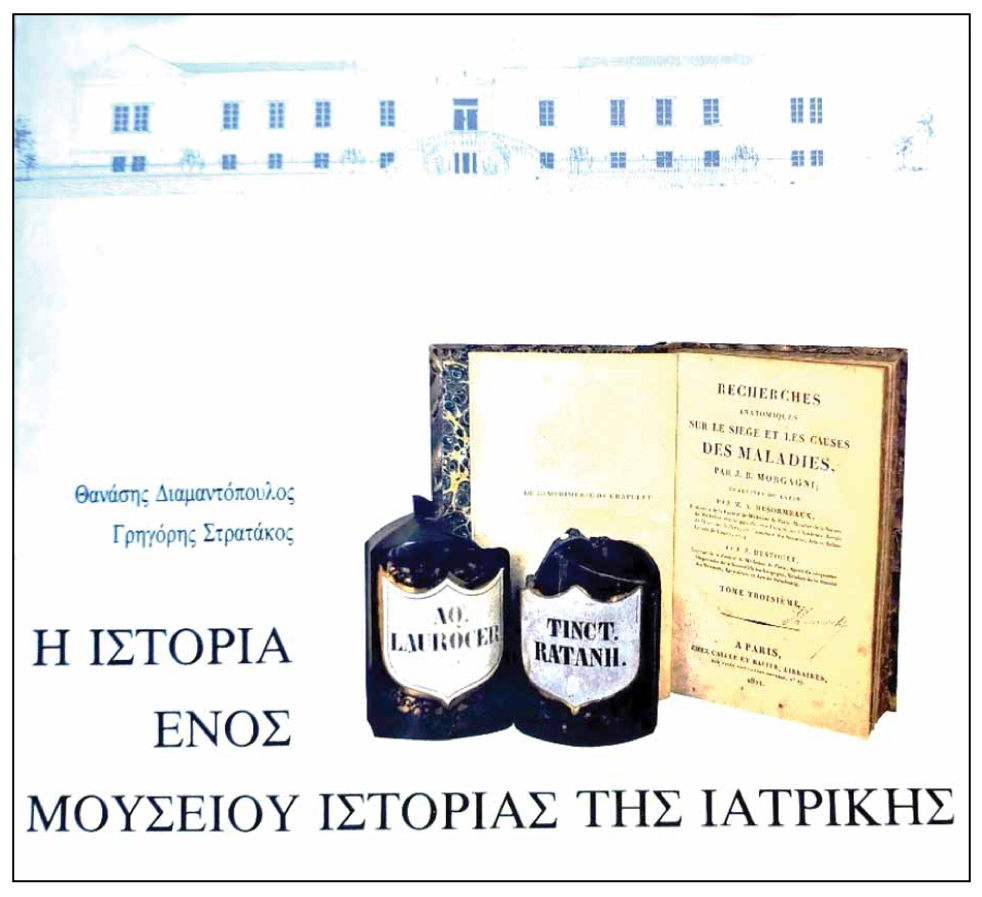

The antique furniture of the Hospital’s Board of Governors was transferred to the new facility and repurposed for use in the office of a Medical School’s professor. When the University’s clinical departments relocated to the Rio Hospital, this furniture was again removed – this time to the professor’s private residence. The Old Hospital also possessed a large and valuable collection of 19th-century glass and porcelain pharmaceutical vials. This collection was looted, and only two broken pieces were later recovered from the refuse outside the building. I salvaged these fragments and featured them on the cover of my book on the History of the Museum of the History of Medicine, (Fig. 9), which had been intended for installation in the basement of the Old Hospital (Fig. 10).

Figure 10. The cover page of the book “The History of a Museum for the History of Medicine”, depicting the last two remaining broken pharmaceutical vials.

Conclusions

a. The willingness of any historian to acknowledge errors made in his previous publications may be perceived by some as a form of academic embarrassment, while by others as an act of intellectual courage. Personally, I consider it a realistic and necessary gesture to uphold the integrity of historical scholarship and protect future researchers from perpetuating inaccuracies.

b. There exists a striking ambivalence in the treatment of local history by institutions and individuals alike. On the one hand, there have been numerous commendable efforts to restore historic public and private buildings. Major initiatives, such as the establishment of the New Archaeological Museum, the restoration of the Roman Odeum, and the conservation of several Byzantine and post-Byzantine churches, serve to safeguard the city’s architectural heritage. Likewise, the publication of numerous works on local history, particularly by Andreas Tsiliras’ “To Donti” Publishing House, testifies to the city’s enduring cultural character.

On the other hand, the systematic neglect and destruction of written and material records – often justified with the unconvincing pretexts of limited space or financial constraints -reveal an institutional and personal disregard, if not outright contempt, for the meticulous work involved in serious historical research.

c. Since its inception in 1910 as a local initiative in Patras, the IEDEP has gradually expanded its geographical remit to encompass the entire Peloponnese by approximately the year 2000. In parallel, Achaiki Iatriki has undergone five significant transformations in its format and one in its publication language. These developments do not necessarily reflect a broader public engagement with the Society’s events or an expanded readership of the journal. However, they do underscore the institution’s remarkable resilience – its capacity to endure across two centuries, through two Balkan Wars, two World Wars, five dictatorships, and multiple regime changes. This endurance owes much to the commitment of its leaders and the dedication of a small yet faithful group of members.

As has aptly been observed:“It is hard to believe long together that anything is worthwhile, unless there is some eye to kindle in common with our own, some brief word uttered now and then to imply that what is infinitely precious to us is precious alike to another mind.” – G. Eliot (1819–1880).

Conflict of interest disclosure

None to declare

Declaration of funding sources

None to declare

Author Contributions

Athanasios Diamantopoulos conceived, designed, wrote, and approved the manuscript.

References

- Diamandopoulos A. Prologue. Achaiki Iatriki. 1988; 6:7. (in Greek)

- Diamandopoulos A. Achaiki Iatriki. 2012 Apr;31(1):87–95. (in Greek)

- Triantafyllou G. Historical lexicon of Patras. 2nd ed. Patras: Petros Koulis Printing House; 1980. (in Greek)

- Politis N. The Patras’ press chronicle 1840–1940. Patras. (in Greek)

- Phorologoumenos (The Taxpayer) newspaper. 1878 Dec 15. Referred by: Diamandopoulos A. Achaiki Iatriki. 1986 Feb;1:Back cover. (in Greek)

- Diamandopoulos A. Achaiki Iatriki. 1986;1:3–8. (in Greek)

- Marasli A. Medicine and doctors at Patras. 1978. p. 232, 293–302, 328. (in Greek)

- Diamandopoulos A, Katsanos A, Moschopoulos G, Vourgarelis Ch, Siamplis D. The impact of the blossoming of Patras port in the evolution of Hellenic radiology. In: Viesca C, Diamandopoulos A, editors. Analecta historico-medica. Mexico City: University of Mexico; 2006. p. 433.

- Diamandopoulos A, Stratakos G. The history of a museum of the history of medicine. Patras: Achaikes Ekdoseis; 1991. (in Greek)