ACHAIKI IATRIKI | 2025; 44(4):184–197

Review

Dimitrios Efthymiou1, Pinelopi Bosgana2, Leonidia Leonidou1,3

1Department of Internal Medicine, University Hospital of Patras, Patras, Greece

2Department of Pathology, General Hospital of Patras, Patras, Greece

3Division of Infectious Diseases, University Hospital of Patras, Patras, Greece

Received: 22 Jun 2025; Accepted: 24 Jun 2025

Corresponding author: Dimitrios Efthymiou, MD, PhDc, Department of Internal Medicine, University Hospital of Patras, 26504 Patras, Greece, Tel.: +30 2613603582, E-mail: efthdim2@gmail.com

Keywords: Granulomatous lymphadenitis, granuloma, lymphadenopathy, adenopathy, sarcoid like reactions

Abstract

Granulomatous lymphadenopathy, or more accurately granulomatous lymphadenitis (GLA), is a histologic pattern of tissue reaction, specifically granulomatous inflammation, in one or more lymph nodes of the human body. It is a type of chronic inflammation characterized by the local aggregation of inflammatory cells, typically organized in an oval-shaped formation. These cell aggregations primarily consist of T-cells, macrophages, epithelioid cells, and giant cells, which are activated by different antigens, leading to granuloma formation (epithelioid cell granulomas). A wide variety of conditions can lead to this reaction, which is encountered more often than expected during diagnostic workups. This underscores the importance of a pattern-based algorithmic approach, combined with the clinical context, to narrow down the pathologic and clinical differential diagnoses. Such an approach contributes to the subsequent clinical management of underlying entities, which may range from infections to malignancies.

Granulomatous Inflammation

Granulomatous inflammation is a type of inflammation that is often organized in an oval-shaped formation within tissues. It is characterized by a focal aggregation of inflammatory cells primarily histiocytes, macrophages, activated macrophages (epithelioid cells) and giant cells (foreign body or Langhans) along with small lymphocytes and plasma cells which typically surround the aforementioned cells [1].

This type of tissue reaction develops in response to persistent, non-degradable stimuli or as a result of hypersensitivity reactions. In most infectious diseases, these two mechanisms appear to overlap. Granulomas serve as a protective mechanism when acute inflammatory processes fail to eliminate causative agents. Their formation follows a stepwise series of events involving a complex interplay between immune cells, causative agents and biological mediators. These areas of inflammation or immunologic reactivity attract monocytes-macrophages, also known as histiocytes when present in tissues, which may fuse to form giant cells or lose their characteristic bean-shaped appearance to become activated epithelioid cells. The centre of the granuloma may occasionally exhibit necrosis [2].

Materials and Methods

Herein, we conducted a literature search in the PubMed database using the keywords ‘Granulomatous lymphadenitis’ or ‘Granuloma’ and ‘Lymphadenopathy’ or ‘Granuloma’ and ‘Adenopathy’ or ‘Sarcoid Like Reactions’. Search was limited to articles written in English and published until February 2025. We ended up choosing 43 articles that were more relevant and concise, in order to keep the references credible but also easily accessible.

Granulomatous Lymphadenitis

Granulomatous lymphadenopathy (GLA), more accurately granulomatous lymphadenitis, is a histologic pattern characterized by granulomatous inflammation in one or more lymph nodes of the human body [3]. Histologically, it is characterized by the collection of epithelioid macrophages with eosinophilic cytoplasm and indistinct cell borders, surrounded by a rim of inflammatory cells (lymphocytes, plasma cells, macrophages) while multinucleated giant cells are often present.

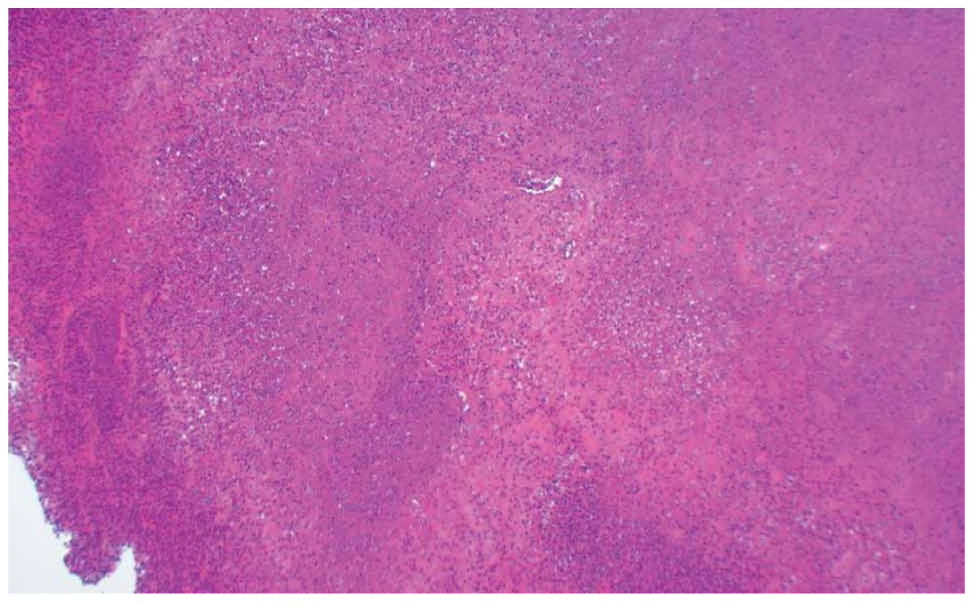

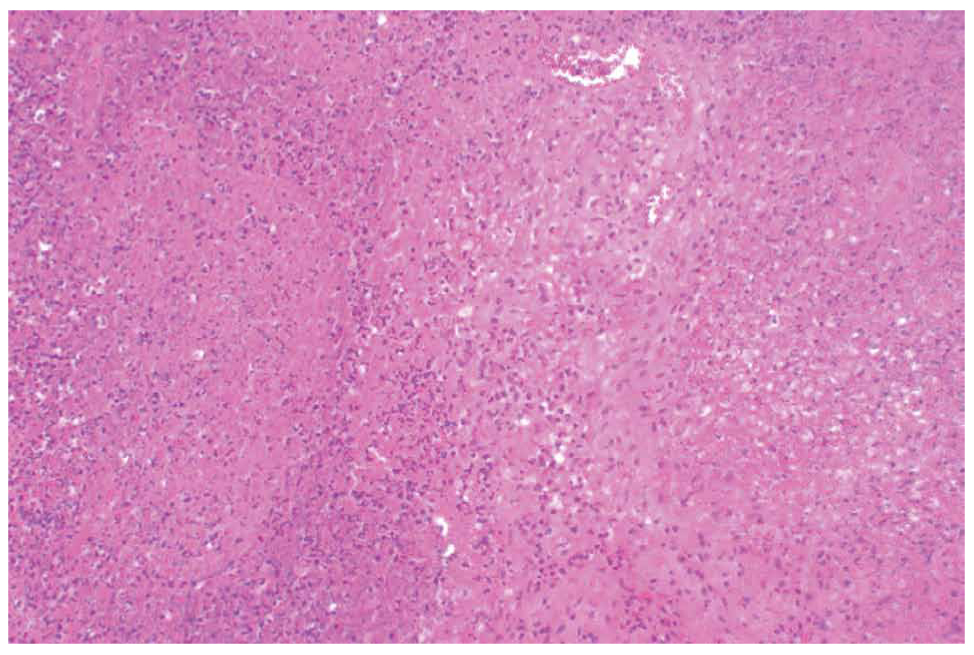

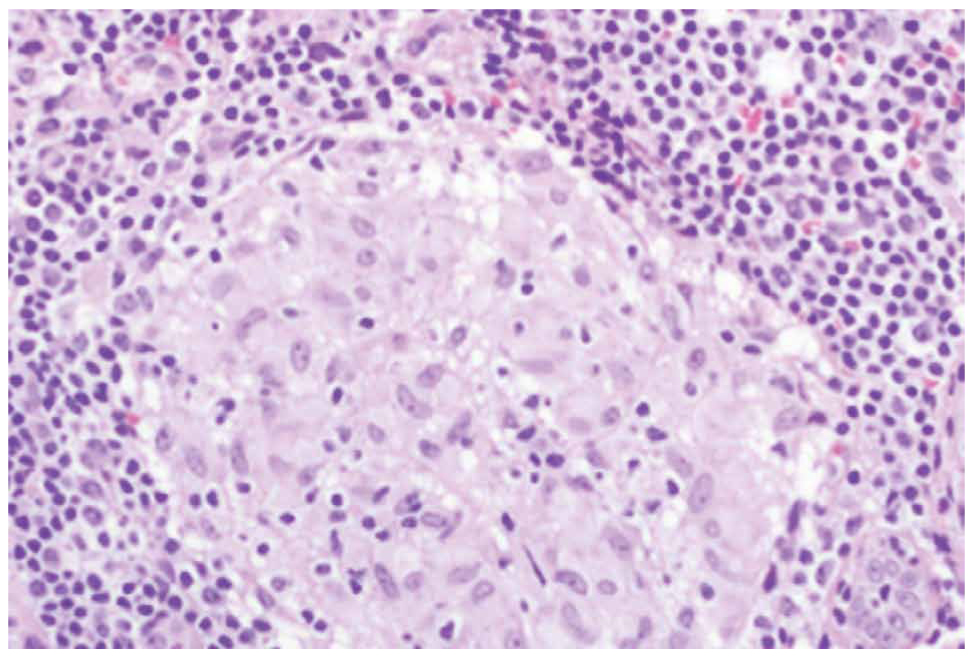

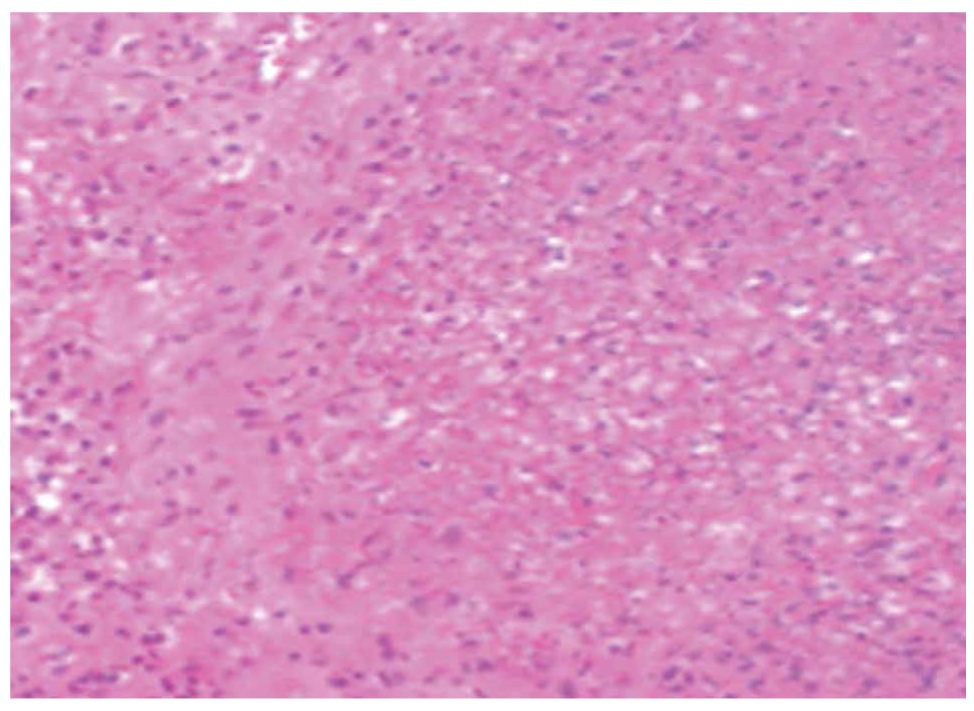

Two main histological subtypes exist: necrotizing and non-necrotizing granulomas [4]. Necrotizing granulomas have a necrotic focus surrounded by a rim of chronic inflammatory cells, including epithelioid macrophages [5] (Figure 1, 2). Although it is not a specific pathological finding, histologic identification of granulomatous inflammation is a useful predictor of diagnostic etiology and can lead to a definitive diagnosis with the aid of ancillary testing, such as special stains and molecular diagnostics. This is because the specific histologic patterns of the granuloma (e.g., foreign-body, necrotizing, non-necrotizing, suppurative, etc.) can help narrow the clinical differential diagnosis when considered alongside the clinical context (Figure 3, 4).

Figure 1. A 67-year-old patient with necrotic granulomatous lymphadenitis (x100).

Figure 2. Necrotic areas surrounded by a rim of epithelioid histiocytes and lymphocytes in the sample of the lymph node (x200).

Figure 3. Non necrotizing granuloma.

Figure 4. Necrotic debris in a necrotizing granuloma.

Factors such as patient’s age and ethnic background, the location of the affected lymph node [whether extracted surgically or sampled via fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) or fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB)], immune status, coexisting HIV infection, past medical history, presenting clinical features and physical examination findings all contribute to determining the underlying cause [3,6].

Histologic Subtypes

The term granulomatous inflammation encompasses a wide spectrum of histologic findings, ranging from well-defined granulomas to loose collections of histiocytes mixed with other inflammatory cells. The latter is typically observed in chronic tissue injury and healing processes. While the loose type is non-specific, well-defined granulomas can offer potential diagnostic insights.

Two forms of well-defined granulomas exist, classified by their etiology: foreign-body giant cell granulomas and immune granulomas. Foreign-body granulomas result from a reaction to inert materials without an adaptive immune response, whereas immune granulomas arise from various etiologies.

Histologically, foreign-body granulomas present as collections of histiocytes surrounding foreign material. Immune granulomas, on the other hand, can be further characterized as necrotizing or non-necrotizing (“naked”). This classification depends on the presence or absence of central necrosis with a palisaded lymphohistiocytic reaction and a surrounding cuff of chronic inflammation. A specific subtype of necrotizing granuloma, in which the central necrotic material has a “cheese-like” consistency, is referred to as caseous necrosis [3].

Additionally, suppurative granulomatous inflammation is another histologic pattern, defined by the presence of epithelioid histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells with a central collection of polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs). It may be associated with both necrotizing and non-necrotizing granulomas. Based on light microscopy alone, suppurative granulomatous inflammation (SGI) represents the end process of various infectious diseases [7].

Lymph Node Biopsy

When obtaining a lymph node biopsy, excisional biopsy remains the gold standard, as it better preserves lymph node architecture and provides sufficient tissue to perform ancillary studies, including microbiologic testing, special stains and immunohistochemistry [8]. However, a 16-year retrospective review by Ng, D. L., & Balassanian, R. analyzing 339 FNABs diagnosing granulomatous inflammation (59% of which involved lymph nodes), demonstrated that FNAB is an excellent, minimally-invasive technique that allows for critical ancillary testing necessary for a definitive diagnosis [9].

Classification & Etiology of Granulomatous Lymphadenitis (GLA)

Granulomatous lymphadenitis is broadly classified into two categories: infectious and non-infectious GLA. Based on histological appearance, granulomas can be further subclassified as necrotizing or non-necrotizing, caseous or non-caseous, and suppurative or non-suppurative [3,5] (Table 1).

A) Non-infectious GLA

Non-infectious causes of GLA include sarcoidosis and sarcoid-like reactions, which encompass a range of diseases that can mimic sarcoidosis both histologically and clinically [10]. Conditions associated with sarcoid-like reactions include:

- Occupational exposure diseases (e.g., silicosis, berylliosis)

- Lymph nodes draining neoplasms

- Lymphomas (Hodgkin’s and non-Hodgkin’s)

- Drug-induced sarcoidosis-like reactions (DISRs)

- Lymph nodes draining areas affected by Crohn’s disease, vasculitis, and other diseases [5]

B) Infectious GLA

Infectious GLA is further classified as suppurative or non-suppurative:

1. Suppurative GLA:

- Characterized by early follicular hyperplasia and sinus histiocytosis.

- Associated with tularemia lymphadenitis, cat scratch disease (CSD), Yersinia lymphadenitis, fungal infections, and lymphogranuloma venereum.

- In tularemia and CSD, monocytoid B lymphocytes (MBLs), T cells, and macrophages contribute to granuloma formation. However, in epithelioid cell granulomas of Yersinia lymphadenitis, MBLs are absent, unlike in CSD.

- Notably, almost all granulomas induced by Gram-negative bacteria contain a central abscess.

2. Non-Suppurative GLA:

● Includes hypersensitivity-type granulomas caused by:

– Mycobacterium tuberculosis

– Atypical mycobacterium infections

– Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) lymphadenitis

– Toxoplasma lymphadenitis (Piringer-Kuchinka lymphadenopathy)

– Leprosy, syphilis, and brucellosis

● Fungal infections (e.g., Cryptococcus, Histoplasma, Coccidioidomycosis, Pneumocystis) may present with both suppurative and non-suppurative granulomas [5]

Non-Infectious GLA

A. Sarcoidosis

Sarcoidosis is a granulomatous, multisystem disease of unknown etiology affecting different organs such as the lungs, skin, kidneys, joints, muscles and eyes [5,11]. It occurs in individuals of all ethnic backgrounds with a higher prevalence in non-smokers, females, African Americans and Scandinavians and typically affects adults aged 30-50 years [11, 12].

Sarcoidosis is a highly heterogeneous disease with phenotypes ranging from acute to subacute and chronic forms. Many patients remain asymptomatic, but approximately 20% develop chronic progressive disease, potentially leading to lung fibrosis [12]. Mortality occurs in 2-4% of cases, primarily due to respiratory failure from pulmonary fibrosis, although cardiac involvement (e.g., sudden cardiac death) is also a rare but serious complication [12].

Clinical and Radiological Features

● Intrathoracic involvement is observed in 90% of patients typically presenting as bilateral hilar adenopathy and/or diffuse lung micronodules, along the lymphatic structures.

● Extrapulmonary manifestations occur in 25-50% of cases and include:

– Skin lesions

– Uveitis

– Liver or splenic involvement

– Peripheral and abdominal lymphadenopathy

– Peripheral arthritis [11]

● Symptoms may range from mild (dry cough, low grade fever, fatigue, weight loss, arthralgia) to severe (Löfgren syndrome, Heerfordt-Waldenström syndrome, lupus pernio, erythema nodosum) [12].

● Hypercalciuria and hypercalcemia occur in ~10% of cases, resulting from increased external production of active vitamin D by macrophages in granulomas [13]. Diagnosis is confirmed when typical clinical and radiological findings are supported by histological evidence of non-necrotic granulomas and by the exclusion of possible alternative diagnoses, since it is a diagnosis of exclusion.

Diagnosis of Sarcoidosis

Sarcoidosis is a diagnosis of exclusion, requiring:

- Compatible clinical and/or radiological findings

- Histological evidence of non-necrotizing granulomatous inflammation

- Exclusion of alternative causes of granulomatous diseases

In some cases (e.g., Löfgren or Heerfordt syndromes) a presumptive diagnosis can be made without a tissue biopsy [11]. Lymphadenopathy is frequently observed, most commonly in pulmonary hilar lymph nodes (93.5%). Cervical (12.2%), axillary (5.2%), and inguinal (3.3%) lymph nodes may also be affected.

Granulomas of sarcoidosis can be distinguished from tuberculosis, fungal infection, silicosis, berylliosis, and Hodgkin’s lymphoma, by their characteristic sharp demarcation, lack of central necrosis and special staining techniques, such as acid-fast and silver impregnation staining in combination with other clinical and laboratory findings [5].

Follicular hyperplasia and sinus histiocytosis may initially resemble nonspecific lymphadenitis. In early stages, these changes give way to well-demarcated granulomas composed of epithelioid cells with scattered multinucleated giant cells, eventually leading to fibrosis and hyalinization [5]. Numerous inclusion bodies may be identified within cytoplasm of giant cells, including:

- Asteroid bodies (composed of calcium, silicon, phosphorus and aluminum)

- Schaumann bodies (round, concentric laminations of iron and calcium)

- Calcium oxalate crystals

- Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS)-positive inclusions, which are yellow or ovoid bodies with uncertain etiology/ pathogenesis [1]

B. Sarcoid Like Lymphadenitis

Ι. Malignancies

Sarcoid-like reactions (SLR) have been described not only with lymphoma [14] but with various solid and hollow organ malignancies including lung cancer [15], breast cancer [16], colorectal [17] and stomach cancer [18] and genitourinary cancers [19]. Although the clinical significance of SLR in cancer patients remains unclear, literature suggests that it is associated with more favorable outcomes [20].

Sarcoidosis-like reactions in malignancy are believed to result from a T-cell-mediated response to soluble tumor antigens, which may be shed by tumor cells or released due to tumor necrosis. These reactions lead to non-caseating epithelioid cell granulomas containing B-cell lymphocytes and sinus histocytes, which are not typically observed in sarcoid granulomas [10, 21].

Regarding sarcoid-like lymphadenitis associated with hematologic malignancies, it is more common in Hodgkin lymphoma than in non-Hodgkin lymphoma [14]. A careful histologic examination can usually confirm the diagnosis, potentially revealing Reed-Sternberg cells in cases of Hodgkin lymphoma. Additionally, lymphocyte marker analysis within the granulomas and ancillary studies may aid in establishing the diagnosis [10].

ΙΙ. Crohn’s Disease

Crohn’s disease is a type of inflammatory bowel disease that can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract and is characterized by skip lesions. Its onset is usually insidious, with clinical features depending on the location and behaviour of the disease (inflammatory, stricturing, or penetrating). The most common symptoms include abdominal pain, chronic diarrhoea (bloody or non-bloody) and weight loss.

Granulomas are present in 15% to 70% of Crohn’s disease patients [22]. Histologically, these granulomas form in draining intestinal lymph nodes and tend to be less well-formed than those seen in sarcoidosis. They are typically non-caseating, which helps differentiate them from intestinal tuberculosis [1,22].

ΙΙΙ. Vasculitis

Both granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA) are types of anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA)-associated vasculitis characterized by systemic vasculitis and granulomatous inflammation in tissues [23]. Although not a common practice, a biopsy of affected lymph nodes in patients with clinical and serological evidence of vasculitis may aid in diagnosis.

Histopathological findings include:

- GPA: Loosely formed granulomas with multinucleated giant cells, necrotic debris and abundant polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs)

- EGPA: Loosely formed granulomas with necrotic debris and eosinophils [24]

A diagnosis of EGPA is supported by a history of asthma, peripheral eosinophilia, and pulmonary, and renal involvement. In contrast, GPA is more likely if the histological findings are combined with upper respiratory tract, pulmonary, and renal involvement along with positive ANCA (PR3+) serology [24].

IV. Occupational-Environmental Exposure

Pneumoconiosis is a spectrum of parenchymal lung diseases caused by the inhalation of (usually) in organic dusts in occupational settings [25]. Silicosis, one of the most common forms, results from inhaling crystalline silica. The typical clinical presentation involves a history of silica exposure, diffuse interstitial opacities and nodules predominantly in the lung apices, often progressing to fibrosis. Lymphadenitis may also be a finding as described in a case by Faisal, Hafsa et al [26]. Pathological lymph nodes (subcarinal, mediastinal and hilar) were identified in that case with an endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA) biopsy revealing granulomatous inflammation with focal necrosis and polarized foreign material, suggestive of silica exposure [26].

Another occupational disease, berylliosis (chronic beryllium disease), is a cell-mediated hypersensitivity disorder caused by exposure to beryllium and beryllium alloys in industrial settings. It leads to non-necrotizing granulomas that are histologically indistinguishable from those of sarcoidosis. These granulomas can be present in pulmonary tissue as well as hilar and mediastinal lymph nodes [27].

V. Drug-Induced Sarcoid-Like Reactions (DISR)

A drug-induced sarcoidosis-like reaction (DISR) is a systemic granulomatous response that is difficult to differentiate from sarcoidosis. It typically occurs 4 to 24 months after the initiation of a new drug [10, 28].

Four major drug categories have been implicated in DISR:

- Interferons

- Highly active anti-retroviral therapy

- Immune checkpoint inhibitors

- Tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF- α) antagonists [28]

The primary method for distinguishing DISR from sarcoidosis is the resolution of clinical findings after discontinuing the offending drug. Otherwise, the clinical manifestations of both conditions are similar.

Histopathologically, DISR granulomas closely resemble those of sarcoidosis, consisting of non-caseating giant-cell epithelioid granulomas surrounded by lymphocytes. Occasional birefringent foreign bodies, asteroid bodies, and Schaumann bodies may be present. The hilar lymph nodes are most commonly affected, similar to sarcoidosis [28].

Treatment may not be necessary if there are no significant clinical findings. However, if intervention is required, discontinuing the causative drug is the preferred approach. If discontinuation is not possible due to the drug’s therapeutic benefits, standard anti-sarcoidosis regimens used in parallel with the drug may be effective [28].

VI. Other diseases

Primary Biliary Cirrhosis

Primary Biliary Cirrhosis (PBC) is a progressive nonsuppurative granulomatous inflammation of the bile ducts, primarily affecting women of reproductive age [2]. Epithelioid granulomas may also be present in various lymph nodes, and PBC can mimic sarcoidosis both clinically and histologically [2, 29].

Adult-onset Still’s disease (AOSD)

Adult-onset Still’s disease (AOSD) is a systemic inflammatory disorder of unknown etiology and pathogenesis. It is typically accompanied by lymphadenopathy in 65% of cases and is histologically associated with intense paracortical immunoblastic hyperplasia. However, literature references indicate that suppurative necrotizing granulomatous lymphadenitis has also been linked to AOSD. For example, Assimakopoulos et al (2012) reported a case of a young adult with mesenteric lymphadenitis associated with AOSD [30].

Kikuchi-Fujimoto Disease

Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease is a benign, self-limiting disorder of the lymphoreticular system with unknown etiology. It predominantly manifests as cervical lymphadenopathy in young women. However, histologically, it is characterized by histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis without any granulomas or caseation. Therefore, it should not be confused as a cause of granulomatous lymphadenopathy [31].

Infectious Granulomatous Lymphadenitis (GLA)

A. Suppurative Granulomatous Lymphadenitis

I) Tularemia Lymphadenitis

Tularemia (Ohara’s disease) is a potentially fatal multisystemic disease affecting humans and animals. It is caused by the facultative intracellular Gram-negative bacterium Francisella tularensis [32]. F. tularensis is classified into three subspecies:

- Tularensis (mainly seen in North America)

- Holarctica (distributed from Europe to Japan)

- Mediasiatica (found in Central Asia)

Infection occurs through arthropod bites, direct contact with infected animal tissues (e.g., during hunting season from November to January) ingestion of contaminated food or water, and inhalation of infectious aerosols, making tularemia a potential bioterrorism threat [5].

Depending on the mode of transmission, tularemia can present in various forms, including ulceroglandular, glandular, oculoglandular (Parinaud oculoglandular syndrome), oropharyngeal, respiratory, and typhoidal [32]. The glandular and ulcerograndular forms are the most common, with skin ulcers appearing primarily on the upper extremities and fingers. Due to regional spread, axillary and elbow lymph nodes are most frequently affected [5]. Lymph node enlargement typically develops within one week after initial skin lesions [1].

Tularemia is characterized by the sudden onset of high fever (38-40oC) headache, flu-like symptoms, and generalized pain, particularly back pain. It can lead to complications such as pneumonia, meningitis, sepsis, or even plaque-like symptoms when transmitted through ingestion.

Histopathologically, tularemia-associated lymphadenopathy progresses through three phases:

- Early (Abscess) Phase (Week 1) – Lymph follicles appear, histiocytic cells gather in the subcapsular sinus, and abscesses with central necrosis form. MBLs are detected adjacent to these lesions.

- Abscess-Granulomatous Phase (Weeks 2-6) – Small epithelioid granulomas with central necrosis fuse to form larger irregular lesions with central abscesses. CD4+ cells predominate over CD8+cells, and multinucleated giant cells appear at the periphery of the granulomas.

- Granulomatous Phase (After week 6) – Necrosis becomes homogenous and may resemble caseous necrosis in the centre of the granulomatous lesion [5].

II. Cat Scratch Disease Lymphadenitis (CSD Lymphadenitis)

Cat scratch disease (CSD) is caused by the Gram-negative bacteria Bartonella henselae and B. quintana, typically following a cat scratch or bite. Many patients do not recall direct contact with a cat. The disease primarily affects immunocompetent children and adolescents, presenting with self-limited fever and painful, localized granulomatous lymphadenopathy (mainly axillary or inguinal or cervical) near the inoculation site. In rare cases, visceral, neurological, and ocular involvement can occur, particularly in immunocompromised individuals.

Immunocompromised patients, such as renal transplant recipients on long-term immunosuppressive therapy, are at risk for severe chronic infections like bacillary angiomatosis [1][33]. Rare cases of mediastinal lymphadenopathy associated with Bartonella Henselae have been reported and disseminated infection or endocarditis should be ruled out in such cases [34].

In immunocompetent patients, CSD is usually self-limiting with adenopathy resolving within 8 to 16 weeks. However, in immunosuppressed individuals, antimicrobial therapy is typically required [33].

Histopathologically CSD lymphadenitis progresses through three stages:

1. Early phase – Reactive follicular hyperplasia, histiocytic proliferation and expansion of lymphoid follicles.

Intermediate Phase – Formation of micro-abscesses with central necrosis, containing clustered neutrophils but lacking epithelioid granulomas. Necrotic debris extends from the subcapsular sinus to the lymph node cortex. Centric fibrinoid necrosis comprises neutrophilic aggregates and progresses to suppuration. MBLs may also be seen.

2. Late phase – Formation of epithelioid cell granulomas, multinucleated Langhans giant cells, and stellate micro-abscesses that eventually coalesce into large irregular geographic abscesses [1].

III. Yersinia Lymphadenitis

Yersinia enterocolitica and Yersinia pseudo-tuberculosis are Gram-negative bacilli from the Enterobacteriaceae family that cause yersiniosis. Following ingestion of the contaminated food or water, the bacteria colonize the distal intestine and spread to mesenteric lymph nodes via lymphatic vessels, leading to various abdominal manifestations, including gastroenteritis, ileitis, and mesenteric lymphadenitis [35].

Clinical symptoms include diarrhea (80%), right lower quadrant pain (50%), nausea, vomiting, fever (38-39˚C), and flu-like symptoms that can mimic acute appendicitis, occasionally leading to unnecessary surgery.

Histopathologically, Yersinia enterocolitica lymphadenitis (lymph nodes of ileum and cecum) is characterized by:

- Non-suppurative epithelioid cell granulomas in germinal centres.

- Suppuration of central granulomas, leading to central micro-abscesses that gradually expand.

- Granulomas composed of epithelioid histiocytes with dispersed, miniature lymphocytes and plasmacytoid monocytes.

- Absence of giant cell reactions and MBL effusion, distinguishing it from granulomas seen in cat scratch disease or lymphogranuloma venereum.

On the other hand, Yersinia pseudotuberculosis infection includes:

- Intense, neutrophilic infiltrates

- Small granulomas with disseminated micro-abscesses

- Central suppuration surrounded by histiocytes (suppurative granulomas), resembling epithelioid aggregates seen in cat scratch disease [1].

IV. Lymphogranuloma Venereum Lymphadenitis

Lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) is a sexually transmitted disease caused by Chlamydia trachomatis, a Gram-negative bacterium. It is generally characterized by a small (2-3 mm), painless genital vesicle or ulcer that spontaneously heals within a short period. This is followed by prominent inguinal lymph node enlargement.

Histologically, in the early stages, LGV lymphadenitis presents with a small necrotic locus with neutrophil infiltration, which subsequently progresses to extensive necrotic foci. These necrotic areas fuse to form stellate micro-abscesses that may coalesce and create a cutaneous sinus tract [1].

B. Non Suppurative

I. BCG Lymphadenitis (BCG-Histiocytosis)

According to World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations, the Bacillus Calmette- Guérin (BCG) vaccination with live attenuated strains is generally safe and effective, particularly in preventing severe forms of tuberculosis (TB), such as childhood TB meningitis and miliary TB disease. It also provides protection against leprosy [36].

The vaccine contains an attenuated strain of Mycobacterium bovis which, despite being the weakest strain globally, retains antigenic activity. After intradermal injection, the organism multiplies at the inoculation site and spreads to regional lymph nodes and systemic organs within hours. As a result, pathological reactions following BCG vaccination, pathological reactions occur at both the inoculation site and regional lymph nodes (mainly axillary and cervical), where subclinical lymphadenitis is common and often resolves spontaneously [37, 5]. Although disseminated BCG infection (BCGosis) is a rare complication, occurring in 0.06 to 1.56 cases per million vaccinations, it is almost exclusively seen in immunocompromised patients (congenital or acquired). Regional disease (BCGitis) may also occur [37,38]. A study by Wang, Jing et al in Shanghai, China reported 56 cases of adverse events following immunization after BCG vaccination from 2010 to 2019, with 51 cases (91.07%) being BCG lymphadenitis. The overall incidence was 173 per 1,000,000 doses [39].

BCG lymphadenopathy is generally smaller than tuberculous lymphadenopathy. Early histological findings include follicular hyperplasia and sinus histiocytosis. Later, epithelioid granulomas without necrosis appear, progressing to granulomas with central coagulation necrosis. Langhans giant cells are rare [5].

II. Tuberculous and Non-Tuberculous Mycobacteria Lymphadenitis

Mycobacteria are the most common etiologic agents of necrotizing granulomas worldwide. Their clinical and radiographic presentation may resemble malignancy or other infections, but they exhibit distinct histologic features.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) is an acid-fast, obligatory aerobe that proliferates within histiocytes. Inhalation of the bacillus induces a granulomatous response in the lungs, leading to a rim of histiocytes and lymphocytes around a necrotic center (Ghon focus). The primary lesion spreads to regional lymph nodes eventually undergoing latency, fibrosis and calcification (Ghon complex). In cases of immune suppression, reactivation may lead to secondary disease with localized cavitation or miliary tuberculosis [3].

Patients with MTB infection typically present with progressively worsening symptoms over weeks to months, including cough, weight loss, fever, night sweats and fatigue, symptoms that may all overlap with sarcoidosis. Radiographic findings of primary TB include hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathy, pleural effusion, and solitary pulmonary nodules. Reactivation TB often shows focal parenchymal opacities, cavitation, pleural involvement, and endobronchial spread, findings that can also be seen with sarcoidosis complicating diagnosis [10].

Histologically, MTB lymphadenitis varies from small epithelioid granulomas resembling sarcoid granulomas, to large caseating necrotic aggregates surrounded by Langhans giant cells, epithelioid cells, and mature lymphocytes [1]. However, MTB lymphadenitis may sometimes present with non-caseating granulomas, while sarcoidosis can exhibit necrotic features in up to one-third of cases [10]. Diagnosis requires confirmation via special stains (Ziehl-Neelsen stain), culture, or polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

Non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) include Mycobacterium kansasii, M. marinum, M. gordonae, M. scrofulaceum and Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare. These pathogens infect both immunocompetent and immunocompromised individuals, resulting in variable clinical presentations. Pulmonary disease is the most common manifestation, but NTM infections may also involve the skin, bones, soft tissues and lymph nodes (typically non-tender lymphadenopathy) [40]. Histologically, NTM lymphadenitis features well-formed granulomas with or without caseous necrosis and histiocytes laden with acid-fast bacilli.[3]However the morphologic differences between MTB and NTM infections on Ziehl-Neelsen staining are unreliable. Culture or molecular assays are required for definitive identification [10].

III. Toxoplasma Lymphadenitis

Toxoplasmosis is a parasitic infection caused by Toxoplasma gondii. Humans, as intermediate hosts, acquire infection through transplacental transmission, ingestion of undercooked meat, contaminated water, or contact with infected cats and their feces. In immunocompetent individuals, toxoplasmosis is often asymptomatic or presents with symptoms resembling infectious mononucleosis. However, in fetuses and immunocompromised patients (e.g., those with AIDS, hematologic malignancies or on immunosuppressive therapy) it may cause myocarditis, pneumonitis, chorioretinitis, encephalitis or even death [5].

Lymphadenopathy is typically localized, firm, and moderately enlarged, most commonly affecting the posterior cervical lymph nodes. Three characteristic histological features include florid follicular hyperplasia, small epithelioid granulomas (mainly at the follicular periphery) and dilated marginal and cortical sinuses with MBLs. Necrosis and Langhass giants cells are rare [1].

IV. Leprosy

Leprosy (Hansen’s disease) is a chronic cutaneous infection caused by Mycobacterium leprae and Mycobacterium lepromatosis [41]. It progresses through multiple stages from tuberculoid (high resistance, few skin lesions) to lepromatous leprosy (low resistance, multiple skin and visceral lesions) [3].

Clinically, leprosy presents with thickened cutaneous nerves and maculoanesthetic skin patches [2]. While lymphadenopathy is usually non-suppurative, acute necrotizing suppurative lymphadenitis has been reported in rare cases [41].

V. Syphilis

Syphilis is a sexually transmitted disease caused by the Gram-negative spirochete Treponema pallidum. Known as “the great imitator” it can present with a wide range of clinical manifestations. Granulomatous inflammation occurs primarily in tertiary syphilis and, rarely, in the secondary syphilis [42].

VI. Fungal Infections

Fungal infections may lead to granulomatous lesions in lymph nodes, which can be either suppurative or non-suppurative [30]. Coccidioidomycosis, also known as Valley fever, is caused by Coccidioides immitis and Coccidioides posadasii, both of which are found in the soil of endemic regions such as southwestern United States. Transmission to humans occurs through inhalation or direct inoculation [3].

The most common presentations include asymptomatic infection or pulmonary coccidiodomycosis, which manifests with cough, fever, and erythema nodosum [2]. In immunocompetent patients, the disease is typically self-limiting, but in immunocompromised individuals, disseminated disease may occur [3]. When endospores form, they trigger a granulomatous, T-cell mediated host response. Recruited histiocytes phagocytize the endospores, which subsequently migrate into regional lymphatics, leading to lymphangitis or lymphadenitis. When fungal stains reveal small yeast forms, the differential diagnosis should include Histoplasma capsulatum and Cryptococcus spp., both of which can also be associated with necrotizing granulomas [3]. In immunocompetent patients, Histoplasma infections in the lungs cause epithelioid cell granulomas with coagulative necrosis. However, in immunosuppressed individuals with fulminant disease, granulomas may be absent [2]. Histoplasmosis may lead to extensive necrosis of the lymph nodes, accompanied by prominent and diffuse hyperplasia of sinus histiocytes [1]. Fungal infections may also be opportunistic infections such as cryptococcosis, aspergillosis, mucormycosis and candidiasis, all of which can involve lymph nodes [1].

VII. Brucellosis

Brucellosis, a zoonotic infection, is caused by Brucella melitensis (most common), B. abortus, B. canisand B. suis. It is primarily transmitted through unpasteurized dairy products. Symptoms include fever, night sweats, chills, headaches, joint pain and lymphadenopathy [43]. Histologically, affected lymph nodes exhibit follicular hyperplasia, epithelioid cell aggregates and non-caseating granulomas [1].

Conclusions

In conclusion, granulomatous lymphadenopathy is a non-specific finding that can be seen in a variety of conditions, including infections, autoimmune diseases, malignancies or drug reactions. Although its presence alone is not diagnostic, it serves as an important clue for investigating potential causes. Its clinical value lies in prompting further workup, such as microbiological testing, imaging, and biopsy, to find the underlying condition and give the appropriate therapy. A thorough understanding of the patient’s history, clinical presentation, and associated findings is crucial for making an accurate diagnosis and guiding appropriate management.

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

Declaration of Funding Sources

None to declare.

Author Contributions

ED conceived the idea; ED, BP performed the literature search; ED, BP wrote the manuscript; BP, LL: critically corrected the manuscript; LL oversaw the study.

References

- Bajaj A. Infective Germination: Granulomatous Inflammation: Lymph Node. J Biol Med Sci. 2018;2(108):2.

- Zumla A, James DG. Granulomatous infections: etiology and classification. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23(1):146–58.

- Shah KK, Pritt BS, Alexander MP. Histopathologic review of granulomatous inflammation. J Clin Tuberc Other Mycobact Dis. 2017;7:1–12.

- Williams O, Fatima S. Granuloma. [Updated 2022 Sep 19]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554586/.

- Asano S. Granulomatous lymphadenitis. J Clin Exp Hematop. 2012;52(1):1–16.

- Alves F, Baptista A, Brito H, Mendonça I. Necrotising granulomatous lymphadenitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2011:2011:bcr1120103548.

- Kinard BE, Magliocca KR, Guarner J, Delille CA, Roser SM. Longstanding suppurative granulomatous inflammation of the infratemporal fossa. Oral MaxillofacSurg Cases. 2016;2(1):14–7.

- Maini R, Nagalli S. Adenopathy. [Updated 2023 Aug 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK558918/

- Ng DL, Balassanian R. Granulomatous inflammation diagnosed by fine-needle aspiration biopsy. J Am Soc Cytopathol. 2019;8(6):317–23.

- Judson MA. Granulomatous Sarcoidosis Mimics. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:680989.

- Sève P, Pacheco Y, Durupt F, Jamilloux Y, Gerfaud-Valentin M, Isaac S, et al. Sarcoidosis: A Clinical Overview from Symptoms to Diagnosis. Cells. 2021;10(4):766.

- Bargagli E, Prasse A. Sarcoidosis: a review for the internist. Intern Emerg Med. 2018;13(3):325–31.

- Baughman RP, Papanikolaou I. Current concepts regarding calcium metabolism and bone health in sarcoidosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2017;23(5):476–81.

- O’Connell MJ. Epithelioid Granulomas in Hodgkin Disease. JAMA. 1975;233(8):886.

- Tomimaru Y, Higashiyama M, Okami J, Oda K, Takami K, Kodama K, et al. Surgical Results of Lung Cancer with Sarcoid Reaction in Regional Lymph Nodes. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2007;37(2):90–5.

- Martella S, Lohsiriwat V, Barbalho DM, Della Vigna P, Bottiglieri L, Brambullo T, et al. Sarcoid-like reaction in breast cancer: a long-term follow-up series of eight patients. Surg Today. 2012;42(3):259–63.

- De Gregorio M, Brett AJ. Metastatic sigmoid colon adenocarcinoma and tumour‐related sarcoid reaction. Intern Med J. 2018;48(7):876–8.

- Kojima M, Nakamura S, Fujisaki M, Hirahata S, Hasegawa H, Maeda D, et al. Sarcoid-like reaction in the regional lymph nodes and spleen in gastric carcinoma: a clinicopathologic study of five cases. Gen Diagn Pathol. 1997;142(5–6):347–52.

- Davanageri RS, Bannur HB, Mastiholimath RD, Patil P V, Patil SY, Suranagi V V. Germ cell tumor of ovary with plenty of sarcoid like granulomas: A diagnosis on fine needle aspiration cytology. J Cytol. 2012;29(3):211–2.

- Steinfort DP, Tsui A, Grieve J, Hibbs ML, Anderson GP, Irving LB. Sarcoidal reactions in regional lymph nodes of patients with early stage non-small cell lung cancer predict improved disease-free survival: a pilot case-control study. Hum Pathol. 2012;43(3):333–8.

- Huh JY, Moon DS, Song JW. Sarcoid-like reaction in patients with malignant tumors: Long-term clinical course and outcomes. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:884386.

- Choudhury A, Dhillon J, Sekar A, Gupta P, Singh H, Sharma V. Differentiating gastrointestinal tuberculosis and Crohn’s disease- a comprehensive review. BMC Gastroenterol. 2023;23(1):246.

- Müller A, Krause B, Kerstein-Stähle A, Comdühr S, Klapa S, Ullrich S, et al. Granulomatous Inflammation in ANCA-Associated Vasculitis. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(12):6474.

- Banerjee AK, Tungekar MF, Derias N. Lymph node cytology in Wegener’s granulomatosis. Diagn Cytopathol. 2001;25(2):112–4.

- Cullinan P, Reid P. Pneumoconiosis. Prim Care Respir J. 2013;22(2):249–52.

- Faisal H, Elkhapery A, Iyer C, Ur Rehman S, Malik H. Silicosis Presenting as Granulomatous Lymphadenitis. Chest. 2022;162(4):A1986–7.

- MacMurdo MG, Mroz MM, Culver DA, Dweik RA, Maier LA. Chronic Beryllium Disease. Chest. 2020;158(6):2458–66.

- Chopra A, Nautiyal A, Kalkanis A, Judson MA. Drug-Induced Sarcoidosis-Like Reactions. Chest. 2018;154(3):664–77.

- Fox RA, Scheuer PJ, James DG, Sharma O, Sherlock S. Impaired Delayed Hypersensitivity in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis. Lancet. 1969;293(7602):959–62.

- Assimakopoulos SF, Karamouzos V, Papakonstantinou C, Zolota V, Labropoulou-Karatza C, Gogos C. Suppurative necrotizing granulomatous lymphadenitis in adult-onset Still’s disease: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2012;6:354.

- Nayak HK, Mohanty PK, Mallick S, Bagchi A. Diagnostic dilemma: Kikuchi’s disease or tuberculosis? BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:bcr2012008026.

- Tuncer E, Onal B, Simsek G, Elagoz S, Sahpaz A, Kilic S, et al. Tularemia: potential role of cytopathology in differential diagnosis of cervical lymphadenitis: Multicenter experience in 53 cases and literature review. APMIS. 2014;122(3):236–42.

- Gai M, d’Onofrio G, di Vico MC, Ranghino A, Nappo A, Diena D, et al. Cat-Scratch Disease: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Transplant Proc. 2015;47(7):2245–7.

- Lovis A, Clerc O, Lazor R, Jaton K, Greub G. Isolated mediastinal necrotizing granulomatous lymphadenopathy due to cat-scratch disease. Infection. 2014;42(1):153–4.

- Fonnes S, Rasmussen T, Brunchmann A, Holzknecht BJ, Rosenberg J. Mesenteric Lymphadenitis and Terminal Ileitis is Associated With Yersinia Infection: A Meta-analysis. Journal of Surgical Research. 2022;270:12–21.

- World Health Organization. BCG vaccine: WHO position paper, February 2018 – Recommendations. Vaccine. 2018;36(24):3408–10.

- Norouzi S, Aghamohammadi A, Mamishi S, Rosenzweig SD, Rezaei N. Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) complications associated with primary immunodeficiency diseases. J Infect. 2012;64(6):543–54.

- Liberek A, Korzon M, Bernatowska E, Kurenko-Deptuch M, Rytlewska M. Vaccination-related Mycobacterium bovis BCG infection. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(5):860–2.

- Wang J, Zhou F, Jiang MB, Xu ZH, Ni YH, Wu QS. Epidemiological characteristics and trends of Bacillus Calmette-Guérin lymphadenitis in Shanghai, China from 2010 to 2019. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2022;18(1):1938922.

- Pennington KM, Vu A, Challener D, Rivera CG, Shweta FNU, Zeuli JD, et al. Approach to the diagnosis and treatment of non-tuberculous mycobacterial disease. J Clin Tuberc Other Mycobact Dis. 2021;24:100244.

- Meena M, Joshi R, Yadav V, Singh P, K S, Pandey G. Case Report: Lepromatous Leprosy Masquerading as Acute Suppurative Lymphadenitis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2023;109(1):50–2.

- Ambrogio F, Cazzato G, Foti C, Grandolfo M, Mennuni GB, Vena GA, et al. Granulomatous Secondary Syphilis: A Case Report with a Brief Overview of the Diagnostic Role of Immunohistochemistry. Pathogens. 2023;12(8):1054.

- Mirijello A, Ritrovato N, D’Agruma A, de Matthaeis A, Pazienza L, Parente P, et al. Abdominal Lymphadenopathies: Lymphoma, Brucellosis or Tuberculosis? Multidisciplinary Approach-Case Report and Review of the Literature. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023;59(2):293.